South Room.—North End.

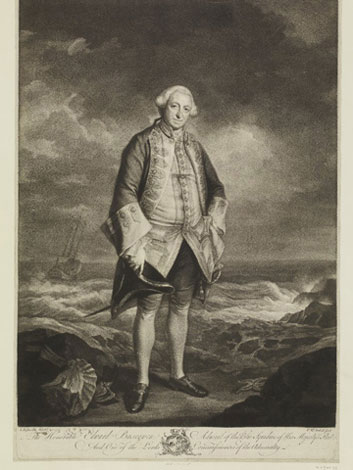

No. 134 "Portrait of Admiral Boscawen"

Mannings # 208

Current title: "Edward Boscawen (1711-61)"

Location: Private Collection

Edward Boscawen (1711-1761) was the third of five sons of Hugh Boscawen, first Viscount Falmouth (c. 1680-1734), politician and courtier, and Charlotte (d. 1754), eldest daughter of Charles Godfrey and his wife, Arabella, sister of the Duke of Marlborough. In 1742, the well-connected Edward married Frances Evelyn Glanville (1719-1805), great-great-niece of the diarist John Evelyn. They had three sons and two daughters and, judging by the surviving letters between husband and wife, enjoyed a happy home-life.

"He ranks among the most important of the navy's officers in the mid-eighteenth century" (ODNB). Promoted to captain in 1741, rear-admiral in 1747, and vice-admiral by the time Reynolds begun this portrait in 1755, Boscawen proved an able leader who took a strong interest in the health and well-being of his men. His unshakeable reputation only strengthened during The Seven Years' War and was followed by further successes in the Mediterranean.

This is the third full-length portrait of a navy admiral in this room (see also No. 106 and No. 111). Boscawen, wearing a flag officer's "undress uniform," stands on a rocky shore strewn with exotic shells—a wind-tossed ship visible in the background.

Further Reading:

Entry for "Boscawen, Edward (1711-1761), naval officer and politician," in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004; online edn. 2008).

Brian Southam, Jane Austen and the Navy (Hambledon and London, 2000).

South Room.—North End.

No. 135 "Portrait of Omai, a native of Ulietta"

Mannings # 1362

Current title: "Omai (Omaih)"

Location: Yale University Art Gallery

Omai was the first Tahitian to visit England. In 1773, he enrolled as supernumerary with Captain Furneaux's ship, Adventure. On board he befriended officer James Burney, brother of novelist Frances Burney. James Burney (1750-1821), who may have instructed Omai in English but certainly acted as his interpreter, described him as "a fellow of quick parts... possessed of many good qualities" (ODNB). Upon arriving in England, Omai was presented at court by Joseph Banks. He was held in high esteem by the king, who granted him a royal pension for the duration of his stay. During his few years in England, Omai "provided elite society with a living example of the noble savage" (ODNB). He was returned to Huahine, near Tahiti, by Cook in 1777. Having built a new life with his store of British goods, Omai died there of natural causes a few years later.

This portrait is a preliminary study rather than a finished work. Omai's costume does not include a turban (unlike the better-known full-length portrait of him by Reynolds), and he wears his long hair loose. The contemporary English fashion of natural, un-powdered hair was just then coming into vogue.

The same oval frame, pose, and long hair are also found in the portrait of the young Viscount Morpeth (No. 136), just to the right. Perhaps this sympathetic juxtaposition by the curators intends to urge a resemblance between the regal Omai and a young member of the peerage.

Further Reading:

Entry for "Omai (c.1753-c.1780), first Tahitian to visit England," in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004).

South Room.—North End.

No. 136 "Portrait of Viscount Morpeth"

Mannings # 948

Current title: "George Howard, afterwards 6th Earl of Carlisle (1773-1848)"

Location: Destroyed

George Howard was the eldest son of Frederick Howard, fifth Earl of Carlisle (1748-1825), and his wife, Margaret Caroline Leveson-Gower (1753-1824). He was styled Viscount Morpeth from his birth until 1825, when he would succeed his father in the earldom. In 1801, he married Lady Georgiana Dorothy Cavendish, the eldest daughter of the famous society hostess and the fifth Duke of Devonshire.

In the 1790s, Morpeth contributed a few literary pieces to The Anti-Jacobin. He also proved an eloquent, if infrequent, parliamentary speaker. In 1812, as a member of the Privy Council, he warmly advocated for "a sincere and cordial conciliation with the Catholics" in Ireland. The motion was defeated.

The painting remained at Castle Howard, the ancestral home of the Earl of Carlisle, until its destruction in World War II. The 1813 exhibit is the only record of its ever having been publically shown outside of the ancestral castle.

Further Reading:

Entry for "Howard, George, sixth earl of Carlisle (1773-1848), politician" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004).

South Room.—North End.

No. 137 "Portrait of a lady and child, W.L."

Mannings # 1585

Current title: "Elizabeth Scott, Duchess of Buccleuch and her daughter, Lady Mary Scott (1769-1823)"

Location: Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry, Bowhill

Although the 1813 Catalogue does not identify the sitters by name, this is a portrait of Elizabeth Scott, the Duchess of Buccleuch (1743-1827), and her daughter, Lady Mary Scott. The Duke and Duchess of Buccleuch were the largest landholders in Scotland.

Born Elizabeth Montagu, the Duchess was the only daughter and heir of George Montagu, created Duke of Montagu in 1766. As the daughter of one duke and the wife of another, Elizabeth may have been deemed an appropriate personage to hang opposite Queen Charlotte in the South Room.

Her husband Henry was educated by philosopher Adam Smith, who acted as the family tutor. Henry and Elizabeth were married by special license in 1767; in this case it was not because the bride was a minor, for Elizabeth was 23, but because the groom was not yet 21. Not long after Henry and his bride settled at Dalkeith Palace outside Edinburgh, the sudden death of his father bestowed upon him the title and vast Buccleuch estates. At a time when other members of the Scottish aristocracy were retreating from public life, the young Duke of Buccleuch was looked to for leadership by the Scottish people.

The placement of this painting beside that of Lord Dunmore in a Highland costume (No. 138) makes for a strong Scottish-themed ending to the exhibit, especially in view of the portrait of Robert Haldane of Gleneagles (No. 86) in the adjacent corner.

Mannings describes a canvas dominated by red hues: the tree is swathed dramatically in "a crimson curtain" while Elizabeth Scott wears "an ermine-lined cloak of a lighter red."

Caveat: Mannings does not link No. 137 in the 1813 exhibit to any of the paintings in his catalogue raisonné of Reynolds' work. This is likely is a mere oversight because #1585 is, by process of elimination, the only likely match for the canvas described in the 1813 Catalogue at No. 137. This same painting was, Mannings confirms, already exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1773 as "A lady, whole length."

Further Reading:

Entry for husband, "Scott, Henry, third Duke of Buccleuch and fifth Duke of Queensberry (1746-1812), landowner and army officer," in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004; online edn. 2009).

South Room.—North End.

No. 138 "Portrait of Lord Dunmore"

Mannings # 1316

Current title: "John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore (1730-1809)"

Location: Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh

John Murray, the fourth Earl of Dunmore, wears the Highland dress of the third Regiment of Foot Guards. The painting, dated 1765, was never collected from Reynolds and not acquired by the family until the nineteenth century.

Murray was a colonial governor of both New York and Virginia. In 1759, he married Lady Charlotte Stewart (d. 1818), daughter of the Earl of Galloway; the couple had nine children. In 1786 he became governor of the Bahamas, strengthening defenses and opening free ports to aggressively expand British-Caribbean trade.

Murray lost favor at court when, in 1793, his daughter Augusta (1768-1830) secretly married the sixth son of George III, Prince Augustus Frederick, in violation of the Royal Marriages Act. Although the marriage was annulled, the royal couple continued to live together with their children until 1801. Murray was dismissed from his post in 1796 and subsequently retired to Ramsgate, Kent, with his wife. Lady Augusta, who retained custody of her children, joined her parents there in 1801, just as the prince accepted a large royal stipend. In 1806, Lady Augusta was granted royal license to use the surname De Ameland instead of Murray, although still forbidden to title herself Duchess of Sussex. The prince remarried in 1731, only after Augusta's death.

Further Reading:

Entry for "Murray, John, fourth earl of Dunmore (1732-1809), colonial governor" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004; online edn. 2009).

Entry for would-be son-in-law, "Augustus Frederick, Prince, Duke of Sussex (1773-1843), sixth son and ninth child of George III and Queen Charlotte," in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004; online edn. 2008).

South Room.—North End.

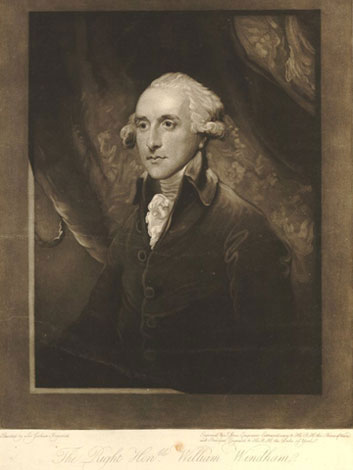

No. 139 "Portrait of the Right Hon. W. Wyndham"

Mannings # 1918

Current title: "William Windham (1750-1810)"

Location: National Portrait Gallery, London

A talented linguist and mathematician, William Windham numbered Edmund Burke, Charles James Fox, and Samuel Johnson (No. 130) among his particular friends. He acted as a pallbearer at Johnson's funeral.

A self-described "politician among scholars and a scholar among politicians," Windham was habitually introspective and even prone to bouts of indecision (ODNB). He was nonetheless a popular figure in polite society and a creditable politician. In 1798, when he was in his late forties, Windham married Cecilia Forrest (1750-1824), who was his own age. The couple had no children.

Major political activities included an appointment as one of the managers of the impeachment of Warren Hastings and a period of active support for the Prince of Wales during the Regency crisis of 1788-9. He became the Secretary at War under Pitt in 1795 and, after some reluctance, supported England's union with Ireland. In 1801 Windham resigned with Pitt over the king's veto of Catholic emancipation. Although he continued in politics until his death in 1810, his ability to articulate both sides of a political question haunted Windham's reputation, making him appear contradictory and fickle.

Further Reading:

Entry for "Windham, William (1750-1810), politician," in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004).

South Room.—North End.

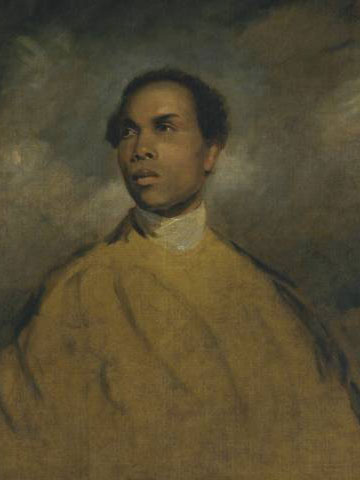

No. 140 "Portrait of a Black servant of Sir Joshua Reynolds"

Mannings # 2003

Current title: "A Young Black"

Location: Menil Foundation, Houston, Texas

The identity of the sitter in this portrait continues to be debated by scholars, who argue about three possible options: 1) a black servant in Samuel Johnson's household named Francis Barber, 2) a servant of Reynolds' mentioned by his pupil James Northcote, and 3) Omai, the Tahitian whose portrait hangs at No. 135.

Whatever the irrecoverable truth, in 1813 the picture's first owner, Sir George Beaumont, lent it to the British Institution as a "Portrait of a Black Servant of Sir Joshua Reynolds"—which is how it is listed in the Catalogue.

It seems significant that the curators opted to place this "Black servant" on the final wall, beneath the former governor of the Bahamas (No. 138). With several navy admirals (No. 106, No. 111, and No. 134), two other black servants (No. 120 and No. 125), the famous Omai (No. 135), and two outspoken abolitionists in this room (No. 104 and No. 115), the question of slavery in the British empire is decidedly in the air of the South Room.

Further Reading:

Edward Said, chapter entitled "Jane Austen and Empire" in Culture and Imperialism (Vintage, 1994).

South Room.—North End.

No. 141 "A Child Asleep"

Mannings # 2036

Current title: "A Child Asleep"

Location: Private Collection

This unfinished study provides an insight into the method that Reynolds used to create fancy pictures: "he would paint the face and nothing more in the first instance; he would then say to himself, 'what will that face and expression be best suited to?', and then he would add the figure to the face—a sure way of securing a correct representation of what he aimed at." (Mannings)

Not only does the 1813 exhibit cleverly resist closure by ending with an unfinished picture, this sleeping child neatly harkens back to the starting wall in the North Room, where hangs "Sleeping Girl" (No. 4).

Middle Room