Middle Room.—South End.

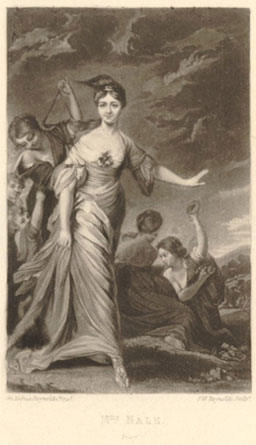

No. 56 "Portrait of Mrs. Mary Hale in the character of the Allegro"

Mannings # 801

Current title: "Mrs. John Hale (1743-1803)" or "Mrs. Hale as Euphrosyne"

Location: Harewood House, Leeds

This painting depicts Mary Hale in the guise of Euphrosyne, a Greek personification of mirth and one of the Three Graces. In Greek mythology, the Three Graces are daughters of Zeus and the Oceanid Euronymo, created to fill the world with pleasant moments and good cheer. The piece is exhibited in the British Institute as "the Allegro," possibly alluding to Milton's pastoral poem L'Allegro, which celebrates the active and joyful life.

Mary was the second daughter of William Chaloner, of Guisborough in Yorkshire, and married Colonel John Hale in 1763, with whom she had 21 children. Her sister Anne married Edward Lascelles, afterwards first Earl of Harewood.

The portrait was commissioned by her husband's cousin, for the redesigned music room at Harewood House. All Three Graces—Aglaea, Euphrosyne, and Thalia—are associated with the divine music of Apollo, to which they would dance in a circle. Mary's portrait remains at Harewood House today.

Middle Room.—South End.

No. 57 "Innocence"

Mannings # 2008

Current title: "The Age of Innocence"

Location: Tate Gallery

This was among the most frequently copied pictures in the nineteenth century (not just of Reynolds). Mannings reports that, "between 1856 and 1893 no less than 323 full scale pictures were made."

Due to its popularity, there has been much debate over the true identity of the sitter. The list of suggested models includes: Reynolds' great-niece Theophila Gwatkin, who was also the model for Simplicity; Miss Anne Fletcher; Anna Maria, daughter of Sir H. W. Dashwood and Mary Helen Graham; and Lady Anne Spencer, youngest daughter of the fourth Duke of Marlborough.

Joseph Grozer's engraving of 1794 was entitled "The Age of Innocence," which is the modern title. It was also exhibited in the 1780s as "A Little Girl."

Further Reading:

Juliet McMasters, "The Children in Emma," in Persuasions 14 (1992): 62-67.

Middle Room.—South End.

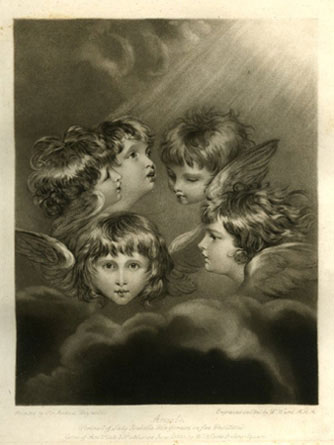

No. 58 "Study of Angels' heads, a daughter of Lord William Gordon"

Mannings # 742

Current title: "Frances Isabella Keir Gordon (1782-1831)" or "Heads of Angels"

Location: Tate Gallery

This painting is inspired by the Italian Baroque, perhaps via Maratta's Infant Christ Adored by Angels. The same sitter's face is shown from different angles to create multiple "heads."

Frances Gordon was the only daughter of Lord William Gordon and his wife Frances Ingram. Her mother was the second daughter of the famous rich beauty Frances Ingram, Viscountess Irwin, known during her widowhood as a political force in Yorkshire and Sussex.

Further Reading:

Entry for "Ingram [née Shepheard, Gibson], Frances, Viscountess Irwin (1734?–1807), landowner and political manager" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford UP, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008).

Middle Room.—South End.

No. 59 "Portraits of Lord Sidney and Col. Ackland, in a landscape, as archers"

Mannings # 41

Current title: "Colonel Acland and Lord Sydney" or "The Archers"

Location: Trustees of the Tetton Heirlooms Estate

Colonel John Dyke Acland (1746-78) was the son of Sir Thomas Acland, third baronet, and Elizabeth Dyke. He served as a soldier in the Devon Militia and, in 1770, married Lady Harriot Fox-Strangways. According to Mannings, the second sitter has been wrongly identified as Thomas Townshend, Baron Sydney of Chislehurst, but is more likely Dudley Alexander Sydney Cosby (c. 1730-74), who was created Lord Sydney of Leix, Baron of Stradbally in 1768. He married Isabella, daughter of the Earl of Howth.

The Earl of Carnarvon is listed as the owner of this picture in the 1813 Catalogue, along with two further pictures loaned to the British Institution (No. 28 and No. 33). The Earl, whose own child portrait is No. 28, was Acland's son-in-law. The Earl's wife, Acland's daughter, had died on 5 March 1813—just a few months prior to the opening of this exhibit.

Acland (front and left) wears green, while Sydney (back and right) wears brown. The fur-lined wrap-around tunics, Acland's prominent sash, and the theatrical tights of both sitters suggest costumes and may be Reynolds' invention. The effect is highly dramatic and, due to the outdated choice of weapon, suggestive of a mythological hunt.

Other theatrically costumed portraits in the retrospective include: No. 25, No. 42, No. 74, and No. 103.

Further Reading:

Entry for "Acland, John Dyke (1747–1778), army officer and politician" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004).

Antje Blank, "Dress," in Jane Austen in Context, ed. Janet Todd (Cambridge UP, 2005), 334-251.

Middle Room.—South End.

No. 60 "Portraits of the Duchess of Gloucester and child"

Mannings # 1903

Current title: "Countess Waldegrave Maria and her daughter, Lady Elizabeth Laura"

Location: Musee Conde, Chantilly

Maria (bap. 1736, d. 1807) was the natural daughter of Sir Edward Walpole and Dorothy Clement, who were not married. She was nonetheless raised by her father as if legitimate. She was twenty-one years younger than her first husband, James Waldegrave, who died in 1763—leaving her a widow with three daughters.

In 1766, Maria married the Duke of Gloucester, brother to King George III, in a secret ceremony. The king remained ambivalent towards the relationship, barely preferring his brother's choice of marriage partner to his keeping a mistress.

Royal scandal truly bloomed in the early 1780s, when Gloucester began an affair with his wife's lady-in-waiting Lady Almeria Carpenter (1752-1809), who soon gave birth to his daughter. Gloucester and his duchess, still attended by Carpenter, spent several years living in Geneva and Italy. By the start of the 1790s, however, the duke and duchess had all but separated and Gloucester sometimes even restricted his wife's access to their children (see No. 78 and No. 102). Maria survived the Duke, who died in 1805.

The composition is not only similar to nearby "Virgin and Child" (No. 55) but even in isolation suggests a Madonna and child—complete with the blue dress traditionally associated with the Virgin Mary and a robe lined with royal ermine for her baby. The gender of the infant sitter does not appear to have distracted Reynolds from the implied comparison (a visual pun on the name "Maria"). As the Catalogue states, Reynolds painted this in 1761, before Maria became a member of the royal family. The location of this painting in the 1813 show, where it is absorbed into a series of religious pictures, seems sensitive to royal feelings while also sympathetic to Maria's memory.

The child shown in this portrait, Lady Elizabeth Laura (1760-1816), married her cousin George who became the fourth Earl Waldegrave. Thus the "Lady Waldegrave" listed in the Catalogue as loaning this picture to the British Institution for the 1813 show was none other than Elizabeth Laura herself.

Further Reading:

Entry for "William Henry, Prince, first Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh (1743–1805)," in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008).

Middle Room.—South End.

No. 61 "Portrait of Mrs. Long"

Mannings # 1143

Current title: "Mrs. Long"

Location: Untraced

Lucy was the daughter of Colonel William Vachell of the Coldstream Guards. She married Richard Long in 1755. Reynolds painted her portrait, and possibly that of her husband, prior to 1760.

This picture is untraced even by Mannings, and there is no image available. This is the first of three "lost" paintings in the 1813 show for which no images are known to exist.

Middle Room.—South End.

No. 62 "St. John, a design for the west window of the chapel in New College, Oxford"

Mannings # 2109

Current title: "New College Window: Adoration of the Shepherds"

Location: Untraced

In 1777, New College of Oxford University hired Thomas Jervais, pioneer of a novel glass-painting technique, to completely renovate the stained glass in their chapel. Reynolds was commissioned to provide the designs. Although these were originally expected in the form of sketches on paper, Reynolds preferred to paint rather than draw—with the oil paintings to be sold after Jervais was finished copying them on glass. Completed by 1785, the windows were significantly altered after a storm in 1848.

As seen in this print of the complete designs, the image of St. John fits in the upper tier, outside left portion of the New College window.

Starting with this painting of St. John, a total of eleven canvases in the British Institution exhibit served as designs for these windows (No. 62 - No. 72). Only the painting for the window's central nativity scene was missing from the 1813 show. It never left Belvoir Castle, where it was destroyed in the 1816 fire. Individually, the designs were also reproduced as prints.

These prints expanded the tall, slender compositions of the original paintings, and in two cases (as here) combined adjacent window designs.

Further Reading:

Michael Wheeler, "Religion," in Jane Austen in Context, ed. Janet Todd (Cambridge UP, 2005), 406-414.

South Room