North Room.—East Side.

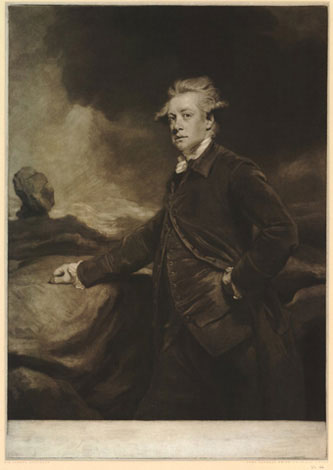

No. 6 "Portrait of Lord Richard Cavendish"

Mannings # 332

Current title: "Lord Richard Cavendish (1752-81)"

Location: The Devonshire Collections, Chatsworth

Second son of the fourth Duke of Devonshire, Lord Richard Cavendish was a member of the House of Commons. The wild coastal rocks in the background may point to his reputation as a fearless traveller.

Richard's older brother, William Cavendish, was the notorious fifth Duke of Devonshire who married the famous Lady Georgiana Spencer whose vivacious and dramatic taste in clothing made her a role model for fashionable society. Although Georgiana shared in her husband's vices and was berated for loose behavior and unsavory company, she ensured the success of many artists simply by her presence or approval, emerging as the leader of a female "battalion" of the Whig party.

This painting still hangs at Chatsworth, the ancestral home of the Duke of Devonshire. Historian Donald Greene pointed to this estate as a possible model for the fictional Mr. Darcy's handsome Pemberley, which is said to lie in Derbyshire and houses the hero's sister, suggestively named Georgiana.

Further Reading:

Entry for brother, "Cavendish, William, fifth Duke of Devonshire (1748-1811), nobleman," in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004).

Entry for sister-in-law, "Cavendish [née Spencer], Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire (1757-1806), political hostess," in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004; online edn. 2010).

Donald Greene, "The Original of Pemberley," Eighteenth-Century Fiction 1 (1988): 1-23.

North Room.—East Side.

No. 7 "Fragment of the late Earl Camden, W.L. Lord Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, and afterwards Lord Chancellor"

Mannings # 1476

Current title: "Charles Pratt, 1st Earl Camden (1713-94)"

Location: Private Collection

Only a fragment of the original whole-length canvas now survives. Mannings describes the painting as now "ruined." In order to give our viewer a sense of the colors in the gallery, the surviving fragment is here imposed atop the engraving.

Son of Sir John Pratt, Lord Chief Justice of the King's Bench, Charles Pratt continued family tradition by becoming a well-renowned attorney and advocate for individual liberty. Once established as Lord Chancellor, he labored to maintain public respect despite searing comments regarding his capricious political ideologies. Charles Pratt encountered particular opposition amidst the Middlesex election of 1768, the American crisis of 1774, and finally the American War for Independence, which caused him to largely withdraw from parliament. He served fifteen years in cabinet, under five different premiers. In 1791, a town in Maine, USA, was named after him. Although active in politics, Pratt had a reputation for physical laziness and for being a bit of a glutton, criticizing any dish that did not satisfy his fastidious tastes.

While law was a respectable semi-genteel profession, attorneys were not regarded as members of elegant society. In Pride and Prejudice, the snobbish Bingley sisters sneer at the "low connections" of the Bennets: "I think I have heard you say, that their uncle is an attorney in Meryton." "Yes; and they have another, who lives somewhere near Cheapside." "That is capital," added her sister, and they both laughed heartily.

Further Reading:

Entry for "Pratt, Charles, first Earl Camden (1714-1794), lawyer and politician," in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004; online edn. 2008).

Brian Southam, "Professions," in Jane Austen in Context, ed. Janet Todd (Cambridge UP, 2005), 366-376.

North Room.—East Side.

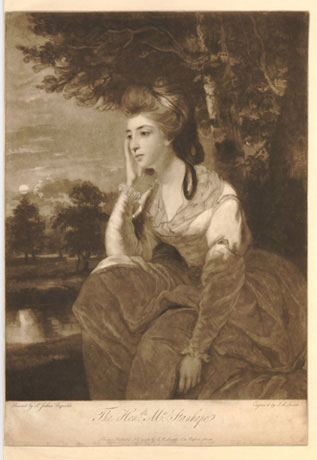

No. 8 "Portrait of the Hon. Mrs. Stanhope"

Mannings # 1699

Current title: "Mrs. Stanhope"

Location: Untraced

Circa 1783, Elizabeth Falconer married Captain Henry Fitzroy Stanhope of the 1st Foot Guard, becoming Mrs. Stanhope. Her husband was the younger son of the second Earl of Harrington and an avid sportsman. Henry Stanhope was such a well-known sportsman and racing fan that the stanhope carriage—a buggy, or light phaeton, with a high back—was named for him.

A critic in the Morning Herald noted that Miss Falconer's "pensive air" in this portrait "is too much in contrast with her usual animation and gaiety" (Mannings).

Although the original portrait remains untraced by Mannings, we chose to hang in our e-gallery a painting "attributed to" Reynolds that sold at Christie's in 1997. Admittedly, it measures 7 inches taller than the portrait recorded in the 1813 catalogue, but it does have the right provenance and image.

Further Reading:

Pat Rogers, "Transport," in Jane Austen in Context, ed. Janet Todd (Cambridge UP, 2005), 325-433.

Sallie Walrond, Looking at Carriages (Pelham, 1980).

North Room.—East Side.

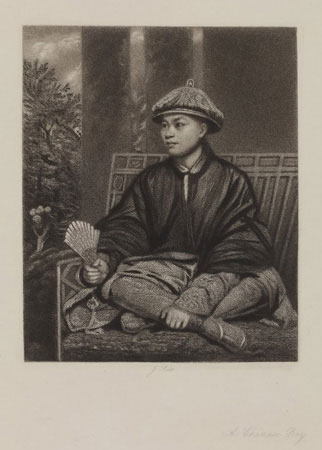

No. 9 "Portrait of a Chinese boy"

Mannings # 1828

Current title: "Wang-Y-Tong"

Location: Knole, Sevenoaks, Kent

Wang-Y-Tong was the Chinese page in the household of the third Duke of Dorset. Known by the Duke and his family as "Warnoton," he was educated at Sevenoaks School at the Duke's urgings.

Chinoiserie—a form of orientalism—overtook European fashionable society in the mid-eighteenth century, blending with the rococo movement. Eager to display their sympathy for Chinese art, England's elite filled their houses with ornate murals of phoenix figures and dragons, collected Imari porcelain, erected elaborate pagodas in their landscape gardens, and proudly posed for portraits in traditional Nehru jackets.

Just two paintings to the right, at No. 13, hangs the "Portrait of the late Sir William Chambers," an architect famed for his Chinese structures at Kew and other English estates.

Further Reading:

Getty Exhibit on Orientalism: http://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/orient/

Hugh Honour, Chinoiserie: The Vision of Cathay (John Murray, 1961).

North Room.—East Side.

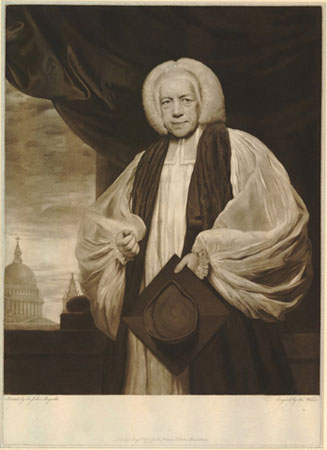

No. 10 "Portrait of Dr. Thomas Newton, Bishop of Bristol"

Mannings # 1338

Current title: "Thomas Newton (1704-82)"

Location: Lambeth Palace, London

Painted in 1773, this portrait shows the Bishop wearing his episcopal habit, with London's St. Paul's Cathedral in the background.

While a preacher in London, Thomas Newton edited and published a variorum edition of Paradise Lost that was exuberantly praised by literary scholars. The prestige and acquaintances garnered by this work aided in securing his position as Bishop of Bristol, though he was not extremely active in the role. His most notable achievement during his tenure as Bishop was preventing the construction of a Catholic chapel in Clifton, a move that maintained a Protestant majority. Later in his career, he attempted to persuade specific artists, including Reynolds, to decorate St. Paul's Cathedral without compensation; he did not succeed.

Further Reading:

Entry for "Newton, Thomas (1704-1782), Bishop of Bristol," in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004).

Irene Collins, Jane Austen and the Clergy (Hambledon, 2002).

North Room.—East Side.

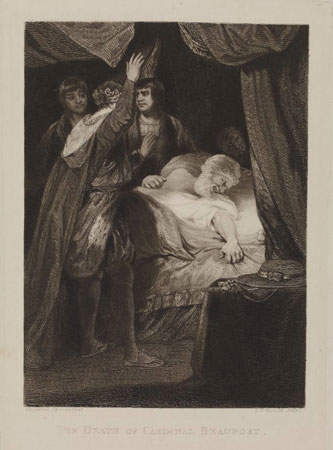

No. 11 "Death of Cardinal Beaufort"

Mannings # 2063

Current title: "The Death of Cardinal Beaufort"

Location: Petworth House, National Trust

Originally commissioned by Alderman John Boydell for his Shakespeare Gallery, where it was exhibited in 1789, this painting is based upon Act III of Shakespeare's Henry VI, Part 2, where Henry VI, Warwick, and Salisbury witness the death of the cardinal.

Since Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery had been located in the same building that in 1813 housed the British Institution, this controversial picture returned, as it were, to the gallery for the Reynolds retrospective, along with "Puck" (No. 54). "King Lear" (No. 41) was apparently never shown in Boydell's gallery.

"Death of Cardinal Beaufort" was extensively reviewed and discussed in 1789. "Criticism centered largely upon the literal presence of the small fiend" visible just behind the cardinal's head. Celebrity landscaper Humphry Repton protested that "Had Shakespeare thought this Evil Spirit necessary, we should have found his name in the Dramatize Personae" (Mannings). Others, including Erasmus Darwin, defended Reynolds' artistic choice, explaining that the creature made Shakespeare's purpose and metaphors more intelligible.

During the 1813 show, this picture was again condemned, this time most loudly by William Hazlitt and Charles Lamb, who pointed to "The Death of Cardinal Beaufort" as demonstrating Reynolds' deficiencies as a subject painter. Their criticism targeted the "establishment acolytes" who promoted Reynolds' work at the expense of his contemporaries (Mannings). Not all artists, in other words, were happy about the exclusivity of the Reynolds exhibit at the British Institution.

North Room.—East Side.

No. 12 "The fortune-teller"

Mannings # 2069

Current title: "Fortune-Teller"

Location: Waddesdon, The National Trust

Mannings sees the composition echoing Caravaggio's Fortune-Teller in the Louvre. The same model from "Boy with cabbage nets" (No. 5) reappears here as the young man in the plumed hat, while the young girl may be the model for "Laughing Girl" (No. 81).

Fortune-telling, although associated with gypsies, remained an acceptable pastime in the homes of the landed gentry, as evidenced in novels from Samuel Richardson's Pamela (1740) to Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre (1847). While Austen's Emma does feature a prominent encounter with gypsies, along with much predicting of fortunes and futures, there is no "fortune-teller" mentioned in any of her fictions.

Nonetheless, Austen's generation grew up with a genre of late-eighteenth-century "fortune-telling" almanacs and poetic miscellanies, marketed especially to ladies, with some works explaining how the arts of palmistry and card reading might be practiced at home.

Another version of this picture, bearing the same title, hangs in the South Room at No. 124.

Further Reading:

Penny Gay, "Pastimes" in Jane Austen in Context, ed. Janet Todd (Cambridge UP, 2005), 337-345.

North Room.—East Side.

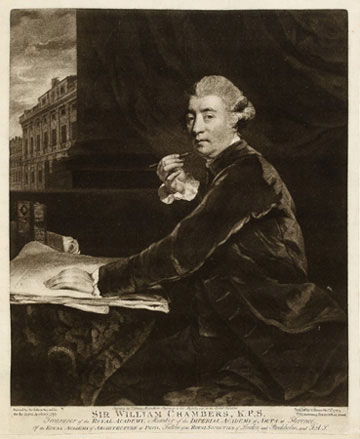

No. 13 "Portrait of the late Sir William Chambers"

Mannings # 346

Current title: "Sir William Chambers (1723-96)"

Location: Royal Academy of Arts, London

An aspiring architect, William Chambers became the first European to study Chinese architecture first hand. This training allowed him to make a large fortune as an early expert on Chinese art and culture, a veritable Sinologist, who travelled throughout Europe as a gentleman designer of Chinese-inspired structures. Occasionally compared to Capability Brown, Chambers strove for a union between art and nature, as reflected in the Chinese gardens at Kew. Later in his career, Chambers simplified the English Palladian villa to create more modern looks, as exemplified in his work at Surrey, Edinburghshire, and Castle Hill. He dedicated the last twenty years of his life to designing Somerset House, finally retiring in 1795.

The proximity of the portraits of Chambers and Wang-Y-Tong (No. 9) seems calculated to emphasize their roles in the Chinoiserie of a prior generation.

Further Reading:

Entry for "Chambers, Sir William (1722-1796), architect," in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004; online edn, 2009).

Alistair M. Duckworth, The Improvement of the Estate: A Study of Jane Austen's Novels.(Johns Hopkins UP, 1971; pbk, 1994).

North Room.—East Side.

No. 14 "Portrait of Lady Melbourne and child"

Mannings # 1080

Current title: "Elizabeth Lamb, Viscountess Melbourne, with her son, Peniston (1770-1805)"

Location: The Trustees of the Firle Estate Settlement

Lady Melbourne's role as a political hostess earned her a reputation as a commanding, vivacious woman. She was nicknamed Themire, the goddess of justice, by Lady Georgiana Spencer, the only woman to outshine her in public and one with whom she maintained a close friendship (Georgiana was married to the older brother of the sitter in No. 6). Lady Melbourne resided in an estate in Piccadilly designed by William Chambers (see the nearby portrait No. 13) and had six surviving children.

Only a year earlier, in 1812, had a satire entitled The Court of Love lampooned her husband, Lord Melbourne, as a "Paragon of Debauchery." Her husband's promiscuous lifestyle prompted several affairs of her own—the most notable being one with the Prince of Wales, who was the presumed father of at least one of her sons. In fact, only the paternity of her son Peniston, whom Mannings identifies as the child in this portrait, was certain. Her remaining children were rumored to have been fathered by men not her husband. The Prince's own portrait hangs, at a discreet remove, in the South Room (No. 95). He is accompanied there by three of the Melbourne children, two of whom were rumored to be his.

By 1813, Lady Melbourne had befriended the poet Lord Byron, who was among the high-profile guests at the opening gala of the Reynolds show. She helped him to put an end to his affair with her daughter-in-law, Lady Caroline Lamb. Lady Melbourne's letters to Byron, written between 1812 and 1816, provide historians with a detailed record of Regency society and manners.

In spite of her romantic liaisons, Lady Melbourne remained relatively immune from social criticism, largely due to her roles as the confidante of the famous Duchess of Devonshire and the friend of the Prince of Wales.

Further Reading:

Entry for "Lamb [née Milbanke], Elizabeth, Viscountess Melbourne (bap. 1751, d. 1818), political hostess and agricultural improver," in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004; online 2008).

Thomas Keymer, "Rank," in Jane Austen in Context, ed. Janet Todd (Cambridge UP, 2005), 387-396.

North Room.—East Side.

No. 15 "Portrait of the Lady Viscountess St. Asaph and her son"

Mannings # 79

Current title: "Sophia Ashburnham, Lady St Asaph (1763-91), with her son, George (1785-1813)"

Location: Baltimore Museum of Art, Maryland

Daughter of Thomas, first Marquess of Bath and Lady Elizabeth Cavendish Bentinck, Sophia married George Ashburnham and died giving birth to their fourth child.

Four years after the death of his first wife Sophia, George Ashburnham married Lady Charlotte Percy (1776-1862). Roughly Jane Austen's contemporary, Charlotte bore George 13 further children. In 1812, George succeeded his father as third Earl of Ashburnham. The Earl is listed in the 1813 Catalogue as the then-owner of this painting of his late wife—a gesture with sentimental resonances.

In her novels, Austen acknowledges pregnancy and childbearing as a genuine source of risk. The death of two of her sisters-in-law during childbirth provided her with tragic proof of such dangers close to home.

The fairly large number of baby portraits in the 1813 show reflects how Reynolds was regularly commissioned to immortalize the young children of England's elite.

North Room.—East Side.

No. 16 "Portrait of Miss Price"

Mannings # 1484

Current title: "Miss Price (1766-1820)"

Location: Hatfield House, Hertfordshire

The sitter, Sarah Bridget Frances Price, was the daughter of Chase Price (1731-77) and Sarah Evelyn Glanville (1735-1826), whose dowry had been a healthy £12,000.

Walpole noted about this picture that it "expresses at once simplicity, propriety, and fear of her cloaths being dirtied, with all the wise gravity of a poor little Innocent" (Mannings). Miss Price was only 10 years old when her father died, coincidentally the same age as Austen's fictional Miss Price, the virtual orphan in Mansfield Park (1814).

Her father, Chase Price, a failed politician and writer of dubious poetry, may have been a member of the Nonsense Club and was certainly a school friend of William Cowper. He was the alleged author of The Torpedo, a crude, sexually explicit poem published after his death. Chase Price juggled complicated financial affairs and found himself repeatedly in debt. "Despite the hair-raising uncertainties of his own business affairs Price continued to handle the finances of his patrons. Surprisingly, his family remained in comfortable circumstances after his death" (ODNB).

Sarah Bridget Frances Price married Bamber Gascoyne (1758-1824), MP for Liverpool, in 1794.

Further Reading:

Entry for "Price, Chase (1731-1777), politician and wit," in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2006; online edn, 2008).

North Room.—East Side.

No. 17 "Children in the Wood"

Mannings # 2044

Current title: "Children in the Wood"

Location: Untraced

Although this is "a fancy," or genre picture, and the model unknown, it hangs among a dense cluster of child portraits in this veritable children's corner of the North Room.

According to a colleague, Reynolds was inspired to paint this piece after one of his child models fell asleep: "It happened, once, as it often did, that one of these little sitters fell asleep, and in so beautiful an attitude, that Sir Joshua instantly put away the picture he was at work on and took up a fresh canvas" (Mannings). When the child shifted positions, Reynolds turned the canvas and sketched the same child again.

The title may invoke an old ballad commonly called "Children in the Wood." Handed down through nineteenth-century children's stories as the tale of the "babes in the wood," the expression has passed into common usage to refer to any event where inexperienced innocents enter unawares into a potentially dangerous situation.

Further Reading:

Juliet McMasters, "The Children in Emma," in Persuasions 14 (1992): 62-67.