North Room.—West Side.

No. 25 "Portrait of Mrs. Baldwyn"

Mannings # 100

Current title: "Mrs. Baldwin (1763-1839)"

Location: Bowood House, Wiltshire

Born in Smyrna, Greece, the daughter of merchant William Maltass, Jane married George Baldwin in 1779. George was fluent in Arabic and traveled through Egypt, Turkey, Greece, and India as a successful merchant. Eventually, he served as the British Consul to Alexandria. Back in England, Jane's exotic features received much notice from society.

Historians interpret Mrs. Baldwyn's costume in different ways, with some describing it as the "national costume" of a Greek lady and others as "a fancy dress" worn at a costume ball given by the King. Other pictures in the show of theatrically costumed sitters include No. 42, No. 59, No. 74, and No. 103.

Further Reading:

Entry for "Baldwin, George (1744-1826)" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004; online edn, 2008).

Antje Blank, "Dress," in Jane Austen in Context, ed. Janet Todd (Cambridge UP, 2005), 334-251.

North Room.—West Side.

No. 26 "Portrait of the late Lady Carysfort"

Mannings # 1492

Current title: "Elizabeth Proby, Lady Carysfort (d. Nov. 1783)"

Location: Elton Hall Collection, Cambridgeshire

Born Elizabeth Osborne, the sitter was the daughter of Sir William Osborne, eighth Baronet, and Elizabeth Christmas. In March of 1774, she became the first wife of politician John Joshua Proby, first Earl of Carysfort (1751-1828). Mannings' date of 1774 suggests this portrait may have been painted in celebration of their wedding.

Elizabeth, who bore her husband three sons and two daughters, died in 1783.

Further Reading:

Entry for husband, "Proby, John Joshua, first earl of Carysfort (1751-1828), politician" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004; online edn, 2008).

Thomas Keymer, "Rank," in Jane Austen in Context, ed. Janet Todd (Cambridge UP, 2005), 387-396.

North Room.—West Side.

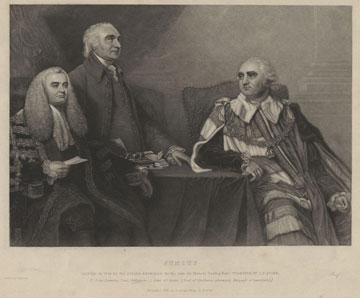

No. 27 "Portraits of the late Marquis of Lansdowne, Lord Ashburton, and Colonel Barré"

Mannings # 543

Current title: "Dunning, John, with Colonel Barré and William, 1st Marquess of Lansdowne"

Location: Private Collection

John Dunning (Lord Ashburton) was a dedicated lawyer and politician who, despite frequent bouts of illness, took part in many high-profile cases and served in the Commons until his death in 1783. He was succeeded by his second son, Richard Barré Dunning. Mannings suggests that the father's likeness in this portrait is posthumous.

William Shelburne, first Marquess of Lansdowne, was a close friend of and political collaborator of John Dunning, whom he met during their mutual dealings with the East India Company. Lansdowne was a controversial politician with provocative rhetorical powers and complex allegiances. In 1777, his French connections and correspondence with Franklin and other Americans rendered him vulnerable to bizarre accusations, almost immediately discredited, that he and other lords planned a conspiracy to assassinate the king. Although he held high political office multiple times, his career was not considered successful.

Further Reading:

Entry for "Dunning, John, first Baron Ashburton (1731-1783), barrister and politician" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004; online edn, 2006).

Entry for "Petty [formerly Fitzmaurice], William, second earl of Shelburne and first marquess of Lansdowne (1737-1805)" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004; online edn, 2010).

Edward Neill, The Politics of Jane Austen (Macmillan and St. Martin's, 1999).

Nicolas Roe, "Politics," in Jane Austen in Context, ed. Janet Todd (Cambridge UP, 2005), 357-365.

North Room.—West Side.

No. 28 "Portrait of Master Henry Herbert, as infant Bacchus"

Mannings # 893

Current title: "Henry George Herbert, afterwards 2nd Earl of Carnarvon (1772-1833)"

Location: Earl of Carnarvon, Highclere Castle

Henry George Herbert was the eldest son of the first Earl of Carnarvon. He became Lord Porchester in 1793. A portrait of his younger brother and mother hangs nearby, at No. 33. Henry married the daughter of Colonel John Dyke Acland (1746-78), whose portrait hangs in the next room, at No. 59.

Young Henry is depicted here as Bacchus, also know as the Greek god Dionysus. Dubbed the Liberator, Dionysus was the god of the grape harvest and wine—associated with ritual madness and ecstasy.

Like "Infant Jupiter" (No. 34), this image is part of a veritable nursery of the gods painted by Reynolds for the proud parents of Britain's youngest elite. Another "young Bacchus" hangs in the middle room, at No. 53.

The earldom of Carnarvon had distant connections to the Austens, since it originated with Mrs. Austen's great uncle, James Brydges, first Duke of Chandos (1674-1744). Brydges obtained the earldom of Carnarvon for his father, who died just before the patent had passed the great seal. As a result, James Brydges was created earl of Carnarvon instead. In 1719 he was further promoted to Duke of Chandos.

Further Reading:

Entry for "Brydges, James, first duke of Chandos (1674-1744), politician and patron of music," in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004; online edn, 2010).

Donald J. Greene, "Jane Austen and the Peerage," PMLA 68.5 (1953): 1017-1031.

North Room.—West Side.

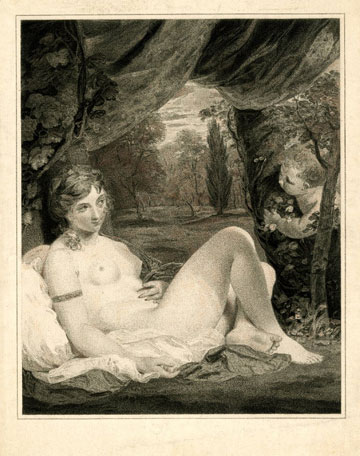

No. 29 "Venus and Cupid"

Mannings # 2174

Current title: "Venus"

Location: Jane and Robert Rosenblum

This painting of the goddess Venus and her son is virtually identical to "Nymph and boy" (No. 75) in the middle room, which is considered a "second version."

According to Mannings, Reynolds incorporated several models into this one image, including the face and hair of a sixteen-year-old girl, the daughter of "his man Ralph," and the body of a beggar-woman with a baby in her lap. Such stories of amalgamation may have given rise to the rumor that even Emma Hart (later Lady Hamilton), sat as a model for some of his depictions of Venus. Painted in the style of Titian, this picture hung at the entrance of Reynolds's own gallery before it was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1785.

Accounts of the Royal Academy exhibit criticized this picture as bordering on indecent: "it may not be amiss to remind the artist who has so wantonly displayed the bosom of a woman in the great room, that a little more decency would have had a much better effect" (General Advertiser, 2 May 1785). Perhaps as a concession to propriety, the curators in 1813 placed this picture, and similarly risqué compositions, above eye level.

Because it is through Venus' intervention that Dido falls in love with Aeneas, the proximity of this picture to "The death of Dido" just below it adds to the pathos of the scene in No. 30.

North Room.—West Side.

No. 30 "The death of Dido"

Mannings # 2065

Current title: "The Death of Dido"

Location: The Royal Collection, London

The death of Dido occurs in the fourth book of Virgil's Aeneid. After Aeneas is shipwrecked at Carthage, the resident queen, Dido, falls in love with him through the intervention of Venus—who hovers on the British Institution's wall just above this scene, at No. 29. In Virgil's story, Dido is devastated when she learns that Aeneas, convinced by Hermes in a dream, must leave her to continue his journey. As her lover's ship sails towards the horizon, Dido builds a funeral pyre of Aeneas's arms, trophies, and their bridal bed. Stabbing herself with his sword, Dido falls on the flames. As Iris, the messenger of Juno, descends to free Dido's soul by cutting a lock of her hair, Anna laments her sister's bitter demise.

The picture drew large and approving crowds when it was first exhibited in 1781 at the Royal Academy, outshining a rival painting by Fuseli in the same show, also entitled "Death of Dido.

In Sense and Sensibility (1811), Austen may invoke this same story when Marianne, like Dido on the cliff tops of Carthage, searches in vain for an impossible view of Willoughby's home at Combe Magna "not thirty" miles away. From the vantage point of the "Grecian temple" atop a hill at Cleveland, Marianne's pathos is momentarily inflated to epic tragedy.

North Room.—West Side.

No. 31 "Count Ugolino and his children in the dungeon, as described by Danté in the 33d Canto of the Inferno"

Mannings # 2172

Current title: "Ugolino and His Children in the Dungeon"

Location: Knole, National Trust

This is a historical subject with literary resonances. A thirteenth-century Italian nobleman, Count Ugolino de Gherardeschi, formed a political alliance with Archbishop Ruggieri and ruled Pisa for a short time. However, he was betrayed by Ruggieri and thrown in prison with two sons and two grandchildren.

Dante chose to incorporate Ugolino's story in the Inferno, presenting him in Hell, gnawing on Ruggieri's head to which his own is frozen. In Dante's poem, Ugolino recounts his nine days in a prison-turned-tomb, explaining how after his children died he resorted to the horrors of cannibalism. The Royal Academy catalogue of 1773 isolated this particular passage from Dante's Inferno to illustrate Reynolds' picture: "I did not weep, I turned to stone inside/ They wept, and my little Anselmuccio spoke:/ "What is it, father? Why do you look that way?"/ For them I held my tears back, saying nothing,/ All of that day, and then all of that night."

While this painting was greatly admired during Reynolds' lifetime, "Ugolino was the object of scathing reviews by William Hazlitt and Charles Lamb when it was exhibited at the British Institution in 1813," with Hazlitt comparing Reynolds' Italian count to a homeless beggar on a city street corner. (Mannings)

North Room.—West Side.

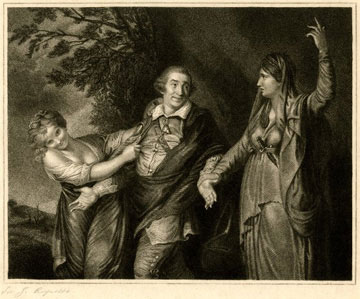

No. 32 "Garrick—between Tragedy and Comedy"

Mannings # 700

Current title: "David Garrick (1716-79)"

Location: Private Collection

Here Reynolds playfully mixes celebrity portraiture with history painting. This portrait of actor David Garrick recalls the "Choice of Hercules," the ancient parable in which Hercules is forced to chose between Virtue and Pleasure. Sheepishly grinning, Garrick yields willingly to the pleadings of Comedy while politely attempting to excuse himself from Tragedy's commands.

After his debut as Richard III in the Fields Theatre in 1741, Garrick became a British sensation. He made up for his short stature through his excess of charm and grace, as well as, an education and business acumen that outpaced the majority of his fellow actors. He became the first theatre manager to incorporate public relations into his performances and was the stage icon of his generation.

In Emma (1815), Austen lightly drops Garrick's name during a scene where the heroine reads aloud some riddles to amuse her father, including a well-known ditty called "Kitty, a fair but frozen Maid." "Yes, papa," says Emma, "We copied it from the Elegant Extracts. It was Garrick's, you know."

In the North Room, Garrick's superstar status is challenged only by the subsequent generation's meteoric thespian Sarah Siddons, who is seated on a throne next to the King (No. 2). Other actresses and performers in the Middle and South rooms include: Mrs. Hartley (No. 47, No. 53, and No. 117); Elizabeth Ann Sheridan (No. 101); Frances Abington (No. 103); and Mrs. Quarrington (No. 116).

Further Reading:

Entry for "Garrick, David (1717-1779), actor and playwright," in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004; online edn, 2008).

Paula Byrne, Jane Austen and the Theatre (Hambledon and London, 2002).

Penny Gay, Jane Austen and the Theatre (Cambridge UP, 2002).

Jocelyn Harris, "Jane Austen and Celebrity Culture: Shakespeare, Dorothy Jordan, and Elizabeth Bennet," in Shakespeare 6.4 (Dec. 2010): 410-430.

North Room.—West Side.

No. 33 "Portrait of Lady Carnarvon and son"

Mannings # 881

Current title: "Herbert, Lady Elizabeth (1752-1826), and her son Charles (1774-1808)"

Location: Private Collection

Lady Elizabeth is depicted with her second son, Charles, who joined the Navy later in life but tragically drowned in 1808. This is the younger brother and mother of nearby "Master Henry Herbert, as infant Bacchus" (No. 28).

For the distant connection between the Carnarvon earldom and the Austens, see information at No. 28.

North Room.—West Side.

No. 34 "Infant Jupiter"

Mannings # 2098

Current title: "Infant Jupiter"

Location: destroyed

In 1816, the original of this painting was destroyed by the same fire at Belvoir Castle that claimed a further eighteen works by Reynolds. This image is of a nineteenth-century copy, likely derived from the print version. Mannings suggests the child's attitude was inspired by a print of Carlo Maratta's Infant Christ Adored by Angels.

According to legend, Jupiter (Zeus, in the Greek) was fed on the milk of the goat Amalthea. As Jupiter's nurse, the she-goat raised him in a cave on Mount Ida in Krete. When the god reached maturity, he created his thunder-shield from her hide and the horn of plenty from her crown. The foundational diet of goat's milk was, some stories allege, responsible for the god's notorious infidelity. Jupiter was said to wield the power of thunderbolts from his domain in the sky and is also associated with the eagle.

Reynolds' portrait comically gives Jupiter's mighty powers to a pouty infant with cherubic baby fat. Reynolds painted a number of baby portraits in this mythological style, including nearby "Master Henry Herbert, as infant Bacchus" (No. 28), creating a veritable nursery of the gods for the proud parents of Britain's elite.

North Room.—West Side.

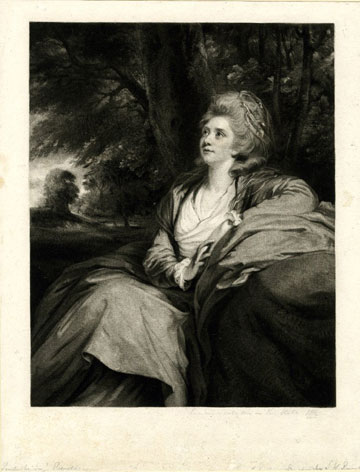

No. 35 "Portrait of the Countess Harcourt"

Mannings # 834

Current title: "Countess Mary Harcourt (1751-1833)"

Location: Private Collection

Mary was the eldest daughter of Reverend William Danby, of Farnley in Yorkshire, and married William Harcourt, third Earl of Harcourt, an army officer and courtier, in 1778.

When William married Mary, she was the widow of Thomas Lockhart of Craighouse, whom she had wed in 1772. She and William had no children. Described as having a "warm temper and small reserve," Mary gained a reputation for meddling in court politics. Domineering, interfering, and sometimes malicious, she repeatedly quarreled with her sister-in-law over the disposal of Harcourt properties

In 1795, Mary reportedly fell out of royal favor after she accompanied the first earl of Malmesbury on his voyage to take Caroline of Brunswick to England for her marriage to George, Prince of Wales. She is said to have offered Caroline "bad advice." Her portrait's location in the North Room, so near the King, suggests reconciliation.

In 1809, William Harcourt succeeded to the titles and estates of his younger brother, including his appointment as master of the horse to the Queen. William then held this post until the Queen's death in 1818. Two years later he would walk as one of the assistants to the chief mourner, the Duke of York, at George III's funeral.

Further Reading:

Entry for husband, "Harcourt, William, third Earl Harcourt (1743-1830)," in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004; online edn, May 2009).

North Room.—West Side.

No. 36 "A girl leaning on a pedestal"

Mannings # 2072

Current title: "Girl Leaning on a Pedestal"

Location: The Iveagh Bequest, Kenwood

This picture was likely shown at the Royal Academy in 1782 as, simply, "Girl." An unidentified sitter leans on her arms. Judging by her clothes, she is a cottager.

The girl bites her thumb, as if in thought. The gesture, seemingly innocent in this young girl, resembles that made by actress Frances Abington while posing in the role of Congreve's famous country ingénue (see No. 103). The biting of one's thumb could, as demonstrated in the opening scene of Romeo and Juliet, hold rude connotations. Whereas the gesture seems merely pensive here, in the Abington portrait it is laden with sexual innuendo.

This picture, which is considered the prime version of many similar compositions, closely resembles "Laughing Girl" (No. 81).

Further Reading:

John Wiltshire, Jane Austen and the Body: "The Picture of Health" (Cambridge UP, 1992).

North Room.—West Side.

No. 37 "A portrait of Lady George Cavendish, W.L."

Mannings # 400

Current title: "Lady Elizabeth Compton (1760-1835)"

Location: National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Known as "Lady Betty," Elizabeth was the daughter of Charles Compton, seventh Earl of Northampton, and Lady Anne Somerset. In 1782 she married Lord George Cavendish, the younger son of the fourth Duke of Devonshire. One of his brothers, Richard, is depicted in canvas No. 6—which hangs just opposite in the show.

Like her brother-in-law opposite, Elizabeth is painted in full length and in an outdoor setting. The "natural" effect created by this woodland setting seems deliberately enhanced by the informal pose, choice of colors, and the marked absence of any sculptures, curtains, or architectural props. Even the stone upon which she leans may be a natural bench or wall.

According to one art historian, the painting may have been an engagement portrait for Elizabeth's husband-to-be, George. Perhaps the pendant necklace she wears is a miniature or silhouette of the groom.

North Room.—West Side.

No. 38 "A girl drawing"

Mannings # 1008

Current title: "Elizabeth Johnson"

Location: Untraced

Elizabeth, or "Betsey," Johnson was the third daughter of Reynolds' sister Elizabeth and her husband William. Betsey married Reverend William Deane of Webbery, Devon, a fellow of All Soul's College, Oxford. However, in all likelihood this portrait is not of Reynolds' niece. Her name connected to this picture only after 1856, and even Mannings thinks it "likely" that the sitter was not Miss Johnson but a paid model.

A studio copy of this picture sold in 2010 as "A Portrait of Lady Emma Hamilton," provocatively naming another possible model or source of inspiration. An official Reynolds portrait of the famous Emma hangs at No. 84. She is also loosely associated with his subject paintings featuring Venus. Mannings' dates of composition ("c. 1780/82") allow the identification and correspond with Emma's early London fame as the muse of painter George Romney.

In 1952, Waterhouse judged the painting to be "shockingly drawn, but really extremely pretty in its slovenly way" (Mannings). The style is uncharacteristically loose for Reynolds—almost Romney-esque. The popular mezzotint of this image, published by Joseph Grozer in 1794, was crisply labeled "Design," and did not identify the sitter.

Irrespective of the model's identity, "A girl drawing" shows one of the so-called female accomplishments. Nonetheless, professional artists like Reynolds were almost always men. Some of Austen's heroines, particularly Elinor Dashwood and Emma Woodhouse, sketch and draw with aplomb. For some critics, this activity suggests a kinship between Austen, the novelist, and particular protagonists as avatar artists.

Further Reading:

Entry for "Hamilton [née Lyon], Emma, Lady Hamilton (bap. 1765, d. 1815), social celebrity and artist's model," in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004; online edn, 2007).

Lance Bertelsen, "Jane Austen's Miniatures: Painting, Drawing, and the Novels," Modern Language Quarterly: A Journal of Literary History 45.4 (1984): 350-372.

Gary Kelly, "Education and Accomplishments," in Jane Austen in Context, ed. Janet Todd (Cambridge UP, 2005), 3252-268.

North Room.—West Side.

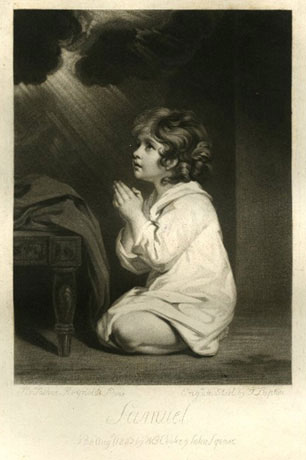

No. 39 "Infant Samuel"

Mannings # 2153

Current title: "The Infant Samuel"

Location: Tate Gallery

A young boy, dressed in his night shift, kneels in prayer at the foot of a bed. Although a ray of light protrudes from behind a cloud above, the carved wooden leg of the bed and a corner of wall behind the boy suggest an interior scene.

There may have been another version that, in 1774, was exhibited by Reynolds' sister Frances at the Royal Academy and which showed a second child.

In the bible story, the sleeping Samuel, then aged 12 or 13, is woken one night by the voice of God. Reynolds domesticates the biblical prophet Samuel with hints of furniture and clothing that literally and figurative bring the ancient story into contemporary relief. Unlike nearby "Infant Jupiter" (No. 34) and "Infant Bacchus" (No. 28), which surround the children of the social elite with elaborate mythological iconography, this humble scene brings ancient piety home in the guise of an unidentified boy.

Novelist Maria Edgeworth, who also attended the 1813 exhibit, particularly praised Reynolds's paintings of children in the show, recalling this picture as "the sublime infant Samuel" (Edgeworth, Letters, 1971).

Further Reading:

Michael Wheeler, "Religion," in Jane Austen in Context, ed. Janet Todd (Cambridge UP, 2005), 406-414.

North Room.—West Side.

No. 40 "Girl and kitten"

Mannings # 2086

Current title: "Girl with a Kitten"

Location: Detroit Institute of Fine Arts

In 1788, Joseph Collyer engraved this painting as a popular print entitled Felina. The print bears these lines of verse: "Fond maid this thy furry care, / An emblem of thyself survey; — / Pleasing and pleas'd, congenial pair, / Both young, and innocently gay! / The hand of time shall change you quite: — / Some trembling MOUSE, some sighing SWAIN, / Shall spring a source of new delight; / The pleasure yours, but theirs the pain."

The visual echoes between the child's face and that of the kitten comically reinforce the kinship between girl and cat that is asserted by the verse inscription of Felina. The comparison is a soft critique and not unlike "Robinette" (No. 45), which likens a girl to a flighty bird.

In Reynolds' time, the keeping of beloved pets was daily contradicted by the manner in which such animals were also used and abused in the culture. A number of portraits in the show feature pet animals, including No. 21, No. 102, No. 50, and No. 103. Those that most closely resemble "Girl and Kitten" in composition are No. 45 and No. 46.

Further Reading:

Diana Donald, Picturing Animals in Britain, 1750-1850 (Yale UP, 2007).

Robert Darnton, The Great Cat Massacre: And other Episodes in French Cultural History (Basic Books, 2009).