North Room.—North End.

No. 1 "Portrait of his Majesty, W.L"

Mannings # 717

Current title: "George III (1738-1820)"

Location: Royal Academy of Arts, London

By 1813, although George III (1738-1820) remained Britain's official King, the country was led by his eldest son, the Prince of Wales, in the role of "Regent" (he would succeed his father as George IV). The Regency, established in 1810, was deemed necessary because George III suffered from recurring bouts of mental illness, which towards the end of his life had become permanent. The illness baffled medical practitioners at the time but may have been caused by porphyria, a blood disease.

In sharp contrast to the public indulgences of the Prince Regent, the King was known for frugal habits and sober conduct. His popular image was that of a plain, honest gentleman, affectionately called "Farmer George" by his people. His arranged marriage to Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1744-1818), who faces her husband from across the gallery at No. 109, proved sensible and successful. The royal couple had 15 children, two of whom died in infancy.

Historical opinions of George III's reign vary and he remains one of the most criticized and controversial of English monarchs. His long reign was marked by many military conflicts and important shifts in the British empire: the Seven Years' War with France; changes in Indian rule; the loss of the American colonies in the American War of Independence; and two decades of war with Napoleonic France which would not conclude until 1815.

Reynolds' portrait depicts the young King as a vibrant leader at 40, before he succumbed to disease and controversy.

Further Reading:

Entry for "George III (1738-1820), king" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004; online edn. 2009).

Roger Sales, Jane Austen and Representations of Regency England (Routledge, 1994).

North Room.—North End.

No. 2 "Portrait of Mrs. Siddons as the Tragic Muse"

Mannings # 1619

Current title: "Sarah Siddons (1755-1831)"

Location: Huntington Art Gallery, San Marino, CA

The daughter of an established stage family, Sarah Siddons [née Kemble] (1755-1831) grew into the greatest tragic actress of her time. This picture, which fanned the flames of the sitter's fame as well as that of the painter, was arguably Reynolds' most extravagantly praised painting and, even in 1813, one of his best-known works.

As a celebrity actress, Siddons was best known for her queenly roles, especially Lady Macbeth. She continued to attract large crowds well into her sixties. In fact, drawn by Siddons' fame, Jane Austen and her brother Henry "planned to go to the theatre" on 22 April 1811 "to see Mrs Siddons but are told she will not be appearing and so give up their seats." Unfortunately for Jane Austen, Siddons "performs after all" that night (Le Faye, Chronology, 400).

Austen's niece Fanny Knight did see the famous actress on 12 May 1812, when she "Dined in haste & went to Covent Garden to see Mrs. Siddons in Belvidera" (Le Faye, Chronology, 423). Siddons officially retired soon thereafter in 1812.

Further Reading:

Entry for "Siddons, Sarah (1755-1831), actress" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford UP, 2004; online edn. 2008).

Paula Byrne, Jane Austen and the Theatre (Hambledon and London, 2002).

Penny Gay, Jane Austen and the Theatre (Cambridge UP, 2002).

North Room.—North End.

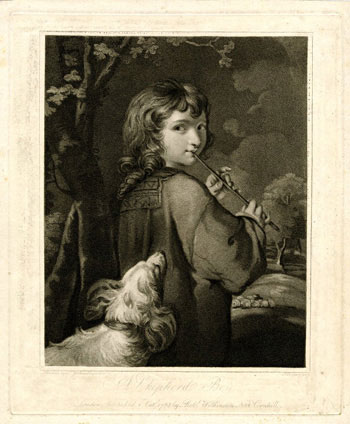

No. 3 "Piping boy"

Mannings # 2156

Current title: "Shepherd Boy"

Location: Private Collection

This is an example of subject painting rather than portraiture. Like the two beside it (No. 4 and No. 5), such paintings were also known as "fancy pictures." Fancies, a term Reynolds used primarily for rival painter Thomas Gainsborough's late work, combined ordinary life with elements from the imagination. Such images often idealized the life of the working poor and were also labeled "sentimental pictures."

In Reynolds' day, the word sentimental was much in vogue, and had not yet fully transitioned from invoking high feeling to superficial or cloying emotion. Painted in 1773, this picture was highly praised as one of Reynolds' "finest" examples of sentimental painting. In 1821 it fetched a record price of £430.10—a hitherto unheard of sum for a fancy by Reynolds.

The Marchioness of Thomond is listed in the Catalogue as the owner of this and twenty-nine further paintings in the show. Born Mary Palmer (1751-1820), she was Reynolds' niece and heir, inheriting many of his paintings. By then she was the second wife of Murrough O'Brien, first Marquess of Thomond. The large Thomond sale of paintings was held in 1821.

North Room.—North End.

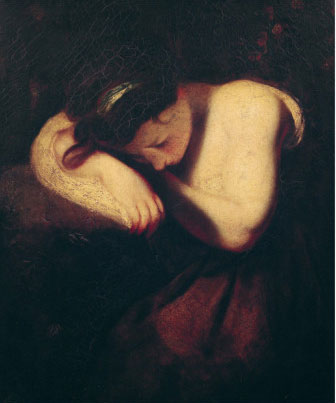

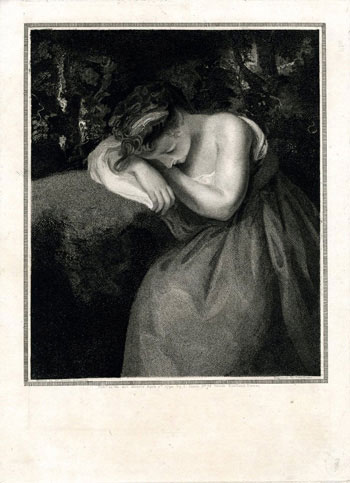

This painting was procured in 1790 by John Wolcot, who pasted the following quote to the back: "Enjoy the honey-heavy-dew of slumber: / Thou hast no figures, nor no fantasies, / Which busy care draws in the brains of men; / Therefore thou sleep'st so sound" (Mannings). The excerpt is taken from Act II of William Shakespeare's Julius Caesar and is spoken by Brutus to the sleeping servant Lucius after the senators meet to conspire against Caesar.

North Room.—North End.

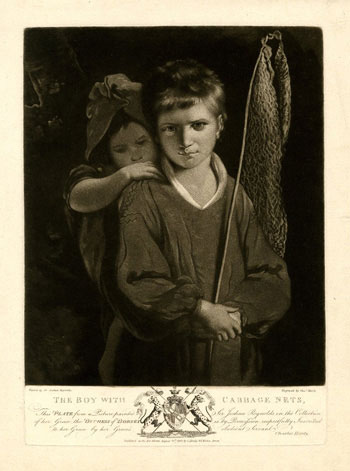

No. 5 "Boy with cabbage nets"

Mannings # 2016

Current title: "A Beggar Boy and His Sister"

Location: The Faringdon Collection Trust, Buscot Park

Appearing in several other paintings including "Infant Samuel" (No. 39), this orphan child seems a favorite model of Reynolds. The poor boy allegedly provided for his younger siblings by teaching them to make and sell cabbage nets.

In this case, a "cabbage net" refers to a mesh bag, often knitted, used for cooking food. The inside was lined with overlapping cabbage leaves before meat or additional vegetables were added to the bag and lowered into a larger pot of water or broth to simmer. When the cabbage net was removed, only the water drained out; this method permitted communal cooking in a single pot of water, even aboard ships.

Further Reading:

Maggie Lane, Jane Austen and Food (Hambledon Continuum, 2007).