About What Jane Saw in 1796

- What was The Shakespeare Gallery, and why did Boydell build it?

- When and why did it close?

- What was the public reaction to The Shakespeare Gallery?

- If the gallery opened in 1789 and closed in 1805, why pick 1796?

- Did Boydell's book-length Catalogue really function as a museum guide?

- Did celebrity actors sit for any of Boydell's paintings?

- What info can a visual reconstruction provide that a catalog cannot?

- Did Austen admire Shakespeare?

- How historically accurate is this digital reconstruction?

- Some findings, curatorial rationale, and caveats

- Cited Works / Site Credits

An enterprising print-dealer, publisher, and alderman named John Boydell opened the first-ever Shakespeare museum in 1789. For a decade and a half, before closing in 1804, his popular "Shakspeare Gallery" showcased contemporary paintings (many were giant canvases with life-sized figures) of well-known scenes from Shakespeare's plays, commissioned from the likes of Reynolds, Romney, Fuseli, Northcote, Opie, Kauffman, Barry, West, and others. This website reconstructs the main interior of Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery as it looked in August of 1796, when novelist Jane Austen visited London.

If the architecture of Boydell's museum seems familiar, this is because his gallery occupied the building at number 52 Pall Mall that would afterwards house the British Institution—host to the 1813 Reynolds retrospective we reconstructed in 2013. Because most of Boydell's paintings, which were dispersed at auction in 1805, are now deemed lost, and the building itself was destroyed in 1870, a digital reconstruction is, once again, the only way to see what Jane Austen, our synecdotal avatar for thousands of eighteenth-century London sightseers, witnessed first hand.

I. What was The Shakespeare Gallery, and why did Boydell build it?

Boydell opened "The Shakspeare Gallery" (he preferred this archaic spelling but in view of the variations found even in eighteenth-century newspaper accounts we've opted for a consistently modern spelling) along up-and-coming Pall Mall on 4 May 1789. The gallery was the first of an ambitious three-part entrepreneurial plan to define Britishness with contemporary art. Boydell aimed to raise the status of history painters and engravers by yoking them to Shakespeare's rising star. The enterprising thespian David Garrick (1717-1779), supreme leader of the new Bardolatry, had made a career out of placing William Shakespeare at the center of British identity. John Boydell (1720-1804) similarly wished to foster a nationalist celebration of Shakespeare that might endorse his brand of art, namely contemporary engravings. The gallery was one of three interlocking projects: the second and third concerned an ambitious new edition of Shakespeare's plays and an elephant folio set of engravings of the gallery's paintings. The engravings would be available for separate purchase as handsome folio prints as well as illustrate the new edition in a smaller format.

Boydell's financial hopes in this multi-part enterprise rested on the business of the engravings, which would publicize and distribute the work of each painter to a wide audience via a then-thriving market for popular prints, especially on the Continent. Following William Hogarth's method of publically displaying paintings as a means of gathering subscriptions for a miniaturized series of engravings, Boydell built a gallery to exhibit the commissioned paintings. Thus The Shakespeare Gallery began as advertisement for a promised edition and its illustrations. Museum before book. While Boydell's capital-intensive scheme failed financially (he claimed to have laid out at least £150,000 on his Shakespeare project), the gallery succeeded during its 15-year run in having great cultural impact.

In June 1788, Boydell leased the site at 52 Pall Mall and hired architect George Dance to build a two-story neoclassical structure that would serve as a proud exhibition hall, with a prominently designed façade to attract foot traffic. The building's central stairway led up to a grand, high-ceilinged gallery where 4,000 square feet of sunlit wall-space in three rooms connected by wide arches could show off the largest canvases to best advantage. There were rooms on the ground floor for changing displays of smaller items—and even a museum shop. In her diary entry of 27 June 1792, novelist Frances Burney records her first visit to Boydell's, mentioning "the long shop" for the purchase of prints and subscriptions and "clerk's desk" in the downstairs areas (2:278).

Boydell commissioned paintings, plus and few key pieces of sculpture, from several dozen contemporary artists. Cautious of duplication, Boydell appears to have assigned each artist a unique scene from Shakespeare. The Shakespeare Gallery opened in May 1789 with 34 canvases displayed in two of its three grand upper rooms; "only two of them are yet open," reported one reviewer (Vickers, 509). The following year, newspapers announced how Boydell's large Shakespeare paintings had "increased to Fifty-five!" (Whitehall Evening Post, 13 March 1790). By 1796, the Boydell annual Catalogue lists 84 large Shakespeare pictures in the three-room gallery, as well as dozens more "Small Pictures" in the lower rooms.

Over the gallery's fifteen-year history, John Boydell commissioned works from leading, and not so leading, artists. Present in the upper gallery in 1796 are works by: James Barry, Josiah Boydell, Mather Brown, Anne Seymour Damer, James Durno, Joseph Farington, Henry Fuseli, John Graham, Gavin Hamilton, William Hamilton, William Hodges, John Hoppner, Angelica Kauffman, Thomas Kirk, William Miller, James Northcote, John Opie, Rev. Matthew William Peters, John Henry Ramberg, Sir Joshua Reynolds, John Francis Rigaud, George Romney, Robert Smirke, Thomas Stothard, Henry Tresham, Benjamin West, Raphael West, Richard Westall, Francis Wheatley, and Joseph Wright.

Back to TopII. When and why did it close?

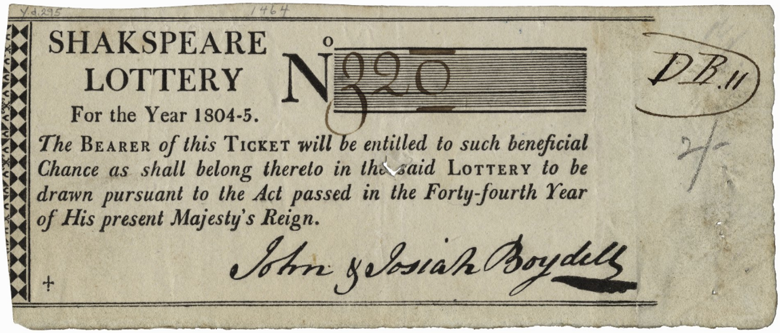

Boydell's art gallery, a landmark "first" in the popular consumption of Shakespeare, proved a fashionable sensation until it fell under the shadow of financial difficulties and had to close in the winter of 1804-5. Delays in the production of the promised edition had dwindled the list of subscribers so that the aging Boydell, forced to compete with the very imitators whom he had inspired, faced bankruptcy. He blamed the war with France for his rising costs, for the decline in the Continental market, and for the project's many delays. Desperate to salvage their business, John Boydell and his partner-and-nephew Josiah Boydell abandoned the original idea of donating the gallery as a legacy to the nation. Instead, they offered up the whole collection for public sale by lottery. What began with 34 canvasses had ballooned, over a fifteen year run, into an inventory of 167 pictures of various sizes. All 22,000 lottery tickets sold, at three guineas apiece, just prior to Boydell's death on 12 December 1804. The lottery was drawn on 28 January 1805.

The lucky winner of the 167 pictures was Mr. William Tassie, a gem and cameo cutter located on Leicester Square. In mid-May 1805, Christie's auction house sold off all the pictures on behalf of Tassie over a period of three days. Just prior to this sale, Josiah Boydell offered Tassie £10,000 for his uncle's inventory, which Tassie declined, countering with an ambitious £23,000 that the young Boydell could not pay. Tassie's expectations were not wildly naïve, since account records show that the Boydells had laid out, over the years, more than £17K for the large pictures alone (roughly half of the total inventory). In the end, these assets did not hold their value: the Christie's sale netted only £6,181 (Pye, 284). The low prices fetched at the 1805 sale may have affected the half-lives of these paintings, many of which simply disappeared from the historical record after this sale.

The building was purchased in 1805 by the British Institution, a private club of artists and connoisseurs who took up Boydell's mission to glorify British art. They redecorated by painting the walls, replacing Boydell's blue-grey with a coat of pale red that looks decidedly pink in Rowlandson's 1808 print of the refashioned interior. The British Institution's 1813 retrospective of the work of Sir Joshua Reynolds was this website's first historical reconstruction. In 1867, the British Institution disbanded and, a few years after that, even the building that Boydell had erected was destroyed.

Back to TopIII. What was the public reaction to The Shakespeare gallery?

Boydell's gallery was a huge hit with a general public eager to pay the entrance fee of one shilling for a unique museum-cum-Shakespeare experience. Boydell encouraged public engagement and may even have planted reviews, allowing one reporter to observe how "the papers teem with remarks upon the paintings in the Gallery of Shakespeare" (Gazetteer, 8 May 1789). Yet the gallery's unprecedented popularity drew controversy, irritating some cognoscenti.

Initially, newspaper updates of the building's construction and rumors about gallery commissions added to the anticipation and curiosity that fed a universal public interest. A weekly London newspaper column devoted itself to gallery news during all of the exhibition season—from May through August. In addition, Boydell and his circle of artists puffed the project with anonymous articles, aiming to increase sales of the advertised edition and engravings.

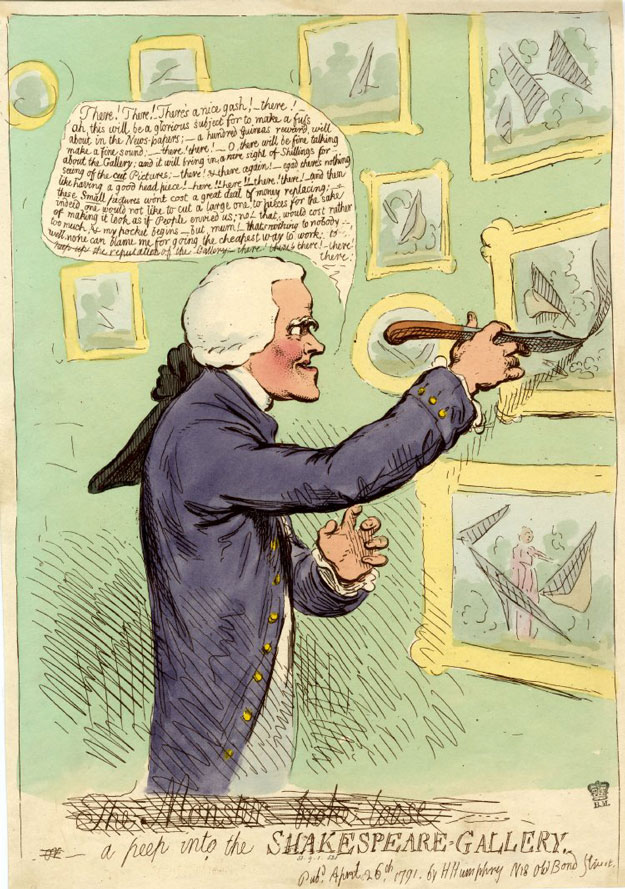

In the wake of a successful opening and publicity splash, the first wave of reviews was generally positive, although a green-eyed James Gillray mocked Boydell's venture as capitalistic rather than artistic with a cartoon entitled "Shakespeare Sacrificed; or, The Offering to Avarice" (1789). The Public Advertiser wrote on 6 May 1789: "the pictures in general give a mirror of the poet," generously predicting that the gallery "will establish and confirm the superiority of the English School." The Times agreed and hailed the Gallery as "the first stone of an English School of Painting," cementing its praise with the prophecy that the gallery's success would place "the name of Boydell in the same rank with the Medici of Italy" (Times, 7 May 1789).

The gallery's heady mixture of painterly styles—differences made all the more evident by the shared subject of Shakespeare—brought with it an invigorating sense of possibility. Canvases by painters of renown hung cheek by jowl with works by relative unknowns and even illustrators who were, professionally speaking, considered mere jobbing artists. Members of the Royal Academy of Arts shared Boydell's walls with non-members. Women shared the space with men, with Angelica Kauffman and Anne Seymour Damer as prominent participating artists (Kauffman, a fellow member of the Royal Academy, blends in while Damer's stonework stands out). The gallery's daring combination of artists and styles was both exciting and unnerving in a democratizing context that already mixed the ambitions of history painting with a populist interest in Shakespeare, who did not yet carry the highbrow label he does today. Added to this was the mix of comedy and tragedy in the choices of scenes for the paintings. One critic surveyed Boydell's mash-up with diplomacy: "such a variety of subjects, it may be supposed, must exhibit a variety of powers; all cannot be the first; while some must soar, others must skim the meadow, and others content themselves to walk with dignity" (Analytical Review, 1788; quoted in Friedman, 73-74).

By April 1794, newspaper reports about the upcoming museum season confirm that, along with other artistic venues mushrooming along Pall Mall, The Shakespeare Gallery had, as art historian Rosie Dias phrases it, "siphoned the artistic talent" away from more established sites such as Somerset House. Boydell's venture was increasingly recognized as a "democratic space indicative of English liberty" (Dias, 53). That is to say, The Shakespeare Gallery's success threatened the elite authority of the Royal Academy. However, Boydell's promised edition was glacially slow to be published (the first volume did not appear until 1791) and, as subscriber patience thinned and novelty wore off, reactions to the gallery predictably grew more critical.

If vandalism is an index of controversy, one incident in April 1791, which involved the violent knifing of some pictures, testifies to tensions even during the gallery's heyday. In the aftermath of the incident, malicious reports spread a rumor that Boydell had done it himself to excite public sympathy and stimulate interest. Cartoonist James Gillray supplied the image (and text) of a greedy Boydell slashing his own pictures:

James Gillray. "

Click to enlarge

Current events periodically pulled the gallery into the newspapers during the 1790s, from holiday accounts of lavish light displays to genuine artistic controversies. For example, the great hullabaloo surrounding the authenticity of the Vortigern manuscript—put forward by Ireland as a lost play by William Shakespeare—embroiled George Steevens, editor of Boydell's new Shakespeare, in a trial of sorts that was held at The Shakespeare Gallery over a period of weeks. This current event was but one of many "political, literary, social and business concerns" that flowed through the gallery, even as it continued to function primarily as a site of artistic display (Dias, 59).

Back to TopIV. If the gallery opened in 1789 and closed in 1805, why pick 1796?

Since Boydell refreshed and expanded his gallery inventory yearly, it would never have been possible for us to show each evolutionary step in the gallery's fifteen-year history. With every annual museum season, which ran from May through August, the gallery lured return visitors with new works. Even the continuously exhibited paintings might be repositioned and said to be "retouched, and considerably improved" (London Times, 29 March 1792). The striking arboreal addition to Joseph Wright's picture at No. 17 (compare the 1794 print by Samuel Middiman, which lacks the dead tree) may even have been an in-house attempt at "improving" that landscape. Early on, visitors were warned with posted notices that pictures were "occasionally withdrawn for the Purpose of engraving," signage that must have added to the gallery's sense of activity (Catalogue 1790, [144]). While we wanted to recapture something of the visceral reality of the Boydell experience, our digital reconstruction had to limit itself to one moment in time.

We opted to frieze The Shakespeare Gallery as it looked during the 1796 museum season because we wanted to portray a significant moment in the gallery's history that coincided, yet again, with a probable visit by Jane Austen. Admittedly, Austen visited London many times—always eager for a gallery, theater, or museum show. She famously confessed to a tendency to people watch even at these artistic venues: "went to the Liverpool Museum, & the British Gallery, & I had some amusement at each, tho' my preference for Men & Women, always inclines me to attend more to the company than the sight" (20 April 1811).

One of Jane Austen's earliest surviving letters is dated 23 August 1796 and was sent from London's "Cork Street," where she stayed with relatives en route to family in Kent. Although Austen was then only twenty, even this 1796 trip was apparently not her first visit to the big city: "Here I am once more in this Scene of Dissipation & vice, and I begin already to find my morals corrupted" (Letters, 5). Provocatively, Austen's brief residence on Cork Street in 1796 places her within an easy ten-minute walk of the gallery. She might also have driven passed it on the way to Astley's equestrian circus ("We are to be at Astley's to night"), another London spectacle that she enjoyed during this same short visit.

Sadly, no further letter survives that, like the one dated 24 May 1813 for the Reynolds exhibition, can testify in Austen's own voice to her visiting Boydell's gallery in Pall Mall on a precise date. Yet it seems inconceivable that her relatives would not take the budding writer, theater enthusiast, and devoted Shakespeare fan to tour the sensational Shakespeare Gallery during at least one such early London visit. We allow that Jane Austen might have seen the gallery earlier than 1796—perhaps during the prior visit hinted at in her London letter. Her family's westward relocation in 1801, from Steventon to Bath, makes a visit to Boydell's gallery during its last years of operation the least likely. In the absence of a confirmed date, however, we picked the likeliest moment during the gallery's zenith that coincided with a London visit by the young Jane Austen—one that placed her within the compass of a short walk.

Importantly, 1796 marks a point of saturation for Boydell's main gallery. The multiple editions of his book-like Catalogue record the expansion of inventory yearly from 1789 through 1796—after that the investment in this bulky form of annual catalog seems to cease for a time (it doubled in girth, from 97 pages in 1789 to 208 pages in 1796, with the paintings in the upper gallery growing in number from 34 to 84). Ann Hawkins, the only scholar to bibliographically compare all extant annual catalogs, reports the slow solidification of the chronological order of the largest pictures. Our digital reconstruction further confirms that the walls of the three rooms in the upper gallery had reached full capacity by 1796. While a few high-profile swaps must have continued to take place annually, it was the ground floor where works rotated most aggressively, especially with smaller canvases, prints, and drawings. During the 1796 museum season, the upper gallery was in full bloom.

Back to TopV. Did Boydell's book-length Catalogue really function as a museum guide?

Yes. The volume of visitors was measured by the gallery's dwindling supply of catalogs, with one London newspaper reporting: "so great was the concourse of the best company to see the Paintings in the Shakspeare Gallery, on Friday last, that, before one at noon, the whole stock of catalogues in the house was exhausted" (St. James's Chronicle, 18-20 March 1791). The imprint on the title page of the 1796 Catalogue of the Pictures, &c. in the Shakspeare Gallery, Pall Mall reads: "Printed for the Proprietors, and sold at the place of exhibition." Visitors were encouraged to purchase a copy of the latest Catalogue to guide them from the vestibule, where Mr. Banks' statue of "Shakspeare seated on a Rock" welcomed arrivals, up the stairs through the exhibit's three rooms where hung the largest "Pictures." Some historians of the gallery think that use of the Catalogue was included in the shilling price of admission (Dias, 50).

Hawkins demonstrates that these catalogs were cheaply, even shoddily, printed and that they recycled sections from a prior year's leftover stock, likely to keep costs low. Instead of annotating the paintings with modern virtual labels, we have provided our e-visitor with facsimiles of the same extracts that Boydell offered his visitors in his 1796 Catalogue—as memory aids to their ready knowledge of Shakespeare. Boydell explains in the first sentence to the first Catalogue of 1789 how each printed scene has one line "marked in Italicks." The italics indicate "the point of Time chosen by the Painter"—the precise moment at which the action of the text is suspended in the corresponding painting (Catalogue, 1789).

This website honors the 1796 edition of the Catalogue as its virtual copy-text—although users should be aware that we have only reproduced a few key sections (ours is an edited-down version of a larger volume). In the primary inventory devoted to the large "Pictures," the 1796 Catalogue lists 83 paintings for which it supplies the relevant text from Shakespeare's plays. After this inventory of large pictures, it next lists three standout works: the showpiece nativity of "The Infant Shakespeare" by George Romney and the two relief sculptures in stone by Anne Damer. Bookending these central items in the 1796 Catalogue are sections not reproduced on our website: at the front, readers found John Boydell's own nine-page "Preface" (unchanged since the grand opening in May 1789); a four-page "Advertisement" dated 15 March 1790 (signed by John Boydell, Josiah Boydell, and publisher George Nicol); and a one-page description of the "Alto-Relievo" statue of Shakespeare by Banks that greeted visitors in the vestibule. At the back: a long list of the 55 "Small Pictures" shown in the rooms on the ground floor; a one-page "Index"; and some advertisements for other Boydell projects. We have reproduced only the Catalogue's title page, its central inventory of large artworks, plus the handy one-page index. For a fuller bibliographical history of all the editions of this Catalogue, we refer you to Hawkins.

Even our slimmed-down version of the 1796 Catalogue in no way resembles the elegant 20-page museum pamphlet produced for the Reynolds retrospective in 1813. Boydell's Catalogue does not just list the paintings (by number, labeled with artist, play title, and scene) but offers a lengthy extract from Shakespeare to match the subject of each painting. The entire gallery was, in essence, the marketing arm of a new Shakespeare edition and catalog heft may argue for a text-based experience. The long extracts provided visitors with the text of a scene that they could review (silently or aloud) while standing in front of the relevant painting.

Back to TopVI. Did celebrity actors sit for any of Boydell's paintings?

No, at least not officially.

In the context of a burgeoning celebrity culture in the eighteenth century, the lack of acknowledged cameos is surprising. Central to the eighteenth-century popularity of Shakespeare had been London's actors and actresses. These celebrities were not merely confined to the stages of Drury Lane and Covent Garden. A vigorous trade in souvenirs, from engraved portraits to ceramic figurines, had indelibly fixed the faces of certain actors to Shakespeare's fictional characters through all manner of objects. In 1796 it was hard to imagine Lady Macbeth without conjuring up Sarah Siddons, Richard III without the face of David Garrick, or Falstaff without visions of a padded James Quinn. Boydell's stock list of available plates in 1803 (including non-gallery pictures) testifies to his own trade in celebrity pinups as a dealer of all manner of popular prints.

With so many of The Shakespeare Gallery's canvases dramatically life-sized, patrons would expect familiar faces on the walls. Whereas the 1813 Reynolds retrospective drew crowds precisely because it publically displayed the private portraits of famous politicians, actors, aristocrats, and royals—all of whom were prominently identified in the exhibition Catalogue—Boydell's history painting project deliberately avoided embracing celebrity portraiture.

Because his approach cut against the grain of public expectation, one anonymous letter in the Gentleman's Magazine dated 11 September 1788 warns that the new Shakespeare Gallery would not satisfy the common need for mere celebrity spotting:

To prevent such expectations from taking root in the minds of tasteless individuals, it would not have been amiss had Messrs. Boydell advertised us that their first instructions to their artists was to forget, if possible, they had ever seen the plays of Shakespeare as they are absurdly decorated in modern theatres, and by no means to adopt ideas of ornament or attitude from any living manager or performers of either sex." (quoted from Vickers, 506)

Boydell, who may have written this cautionary puff himself, set his gallery up as a corrective alternative to the popular theater, warning of the "anachronisms" and "discordant devices" of the playhouse. Boydell's approach, however, did not intend to insult the acting profession: "By no means. Our theatric stars only glitter while they shoot; when fixed, their brilliancy is gone" (Vickers, 506). In this manner, Boydell neatly sealed his history-painting spectacular off from live-action Shakespeare.

Yet it must have been hard to keep that lid on tightly. While for aficionados of history painting any flash of recognition might be anachronistic, breaking the spell of the painter's illusion, for most fans of Shakespeare the celebrity of actors like Siddons, Jordan, and Kemble added to The Bard's thrill. In spite of Boydell's directives to the contrary, some modern curators and historians still claim to spot resemblances between the characters in the Boydell paintings and real-world actors. Surely the possibility of recognizing a look or stance added, then as now, to the frisson of a gallery viewing.

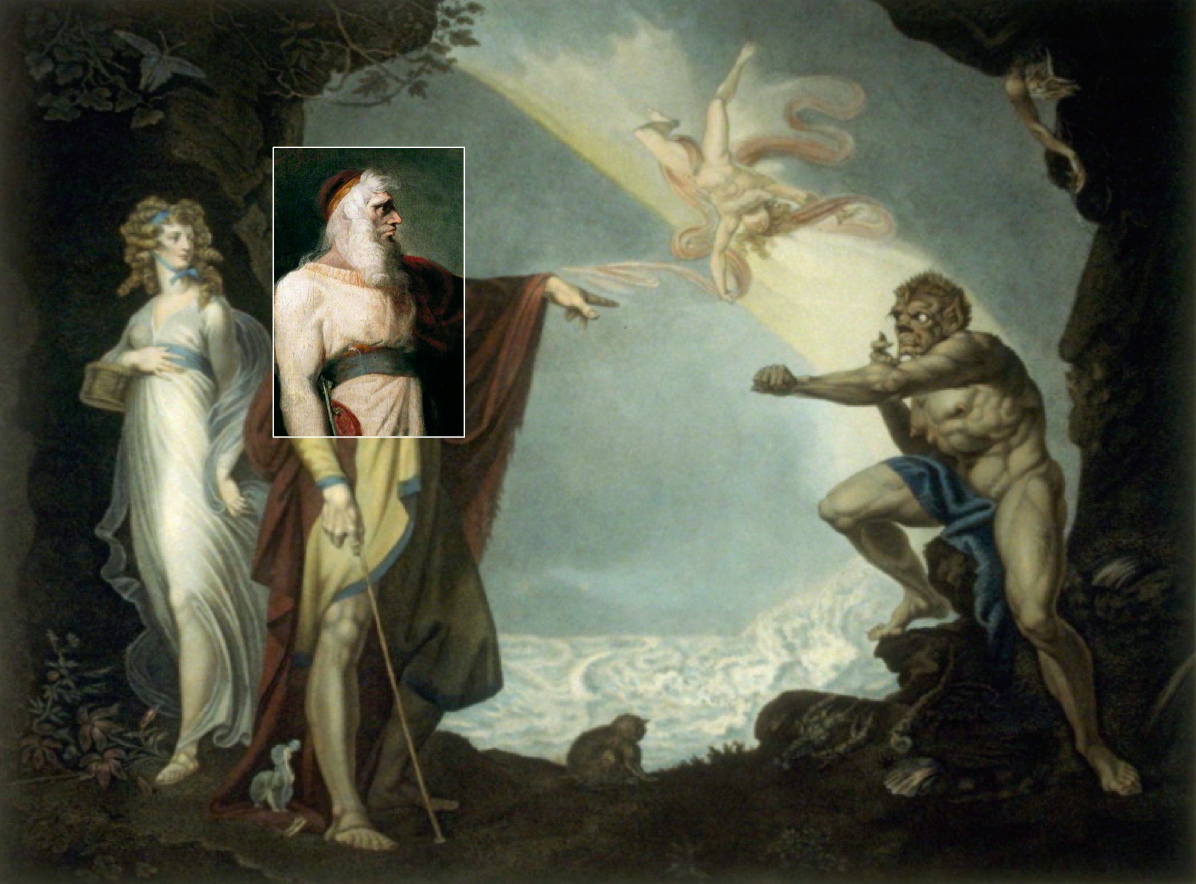

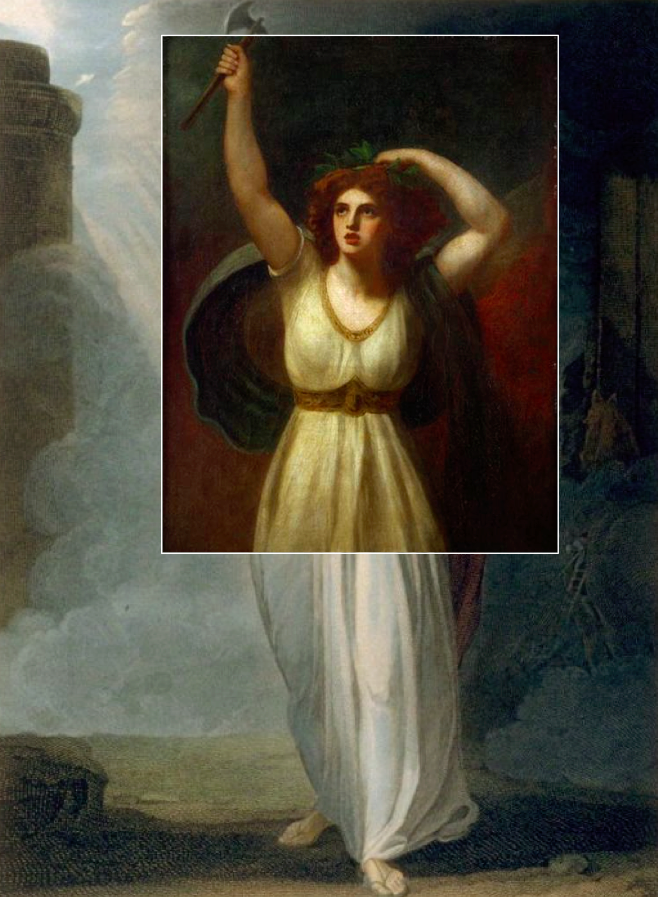

History painters did, of course, use live models. Contemporary accounts suggest that Sir Joshua Reynolds, for example, hired a laborer to sit for his dying Cardinal in No. 23: "He had now got for his model a porter, or coal heaver, between fifty and sixty years of age, whose black and bush beard he had paid for letting grow" (Mannings, 1: 525). Similarly, a real baby reputedly sat for George Romney's infant Shakespeare while, many suggest, Romney used Emma Hart as the model or inspiration for Nature in that same nativity scene—and again for his portrait of the raving Cassandra, which hangs opposite at No. 75. While history painters frequently used real people as models, a sitter's anonymity safeguarded the universality of the resulting image. In the case of Emma Hart, of course, a model's growing fame could eventually complicate history painting's simple realism.

Back to TopVII. What info can a visual reconstruction provide that a catalog cannot?

This website allows a modern viewer to see Boydell's gallery in situ—and for the first time since its closing in 1804. Historians have long acknowledged the cultural importance of The Shakespeare Gallery and tracked its influence on museum culture and Shakespeare reception by means of the Boydell edition, engravings, surviving catalogs, and print reviews. As Hawkins points out, however, the bulk of that book-based scholarship has looked backwards upon the gallery through the lens of its end-products—constructing an idea of how the gallery looked at its close through the accumulated illustrations in the 1803 elephant folio or in the list of the 1805 Christie's sale. Our e-gallery adds to that body of knowledge with an immersive reconstruction that makes it possible to "see" Boydell's gallery during the peak year of 1796.

Our reconstruction makes visible the substantial difference between encountering these images as an exhibition of paintings and viewing them as bound plates in a book. Most obviously, of course, when colored oils of varying sizes are translated into smaller black and white engravings of relative uniform shape and appearance, the resulting prints narrow the gaps of stylistic difference. In addition, the arrangement of the paintings in the gallery in 1796 (as recorded in the annual catalogue for that year) does not match the order of their corresponding plates in the 1803 elephant folio; it is not even close. For example, the gallery exhibition separates the three striking instances where a painter interprets multiple moments in a scene (Fuseli No. 10 and 58; Boydell 48 and 78; and Northcote 27 and 76). In the bound folio, such twin interpretations are paired, to show the immediate unfolding of these scenes, but in the gallery these sequential pictures hung at great remove from their mates. The elephant folio contains a total of 100 plates, whereas the gallery in 1796 displays only 86 works of art. Three of the artworks present in 1796 were not reproduced as folio engravings, namely the two Pucks by Fuseli and Reynolds (Nos. 41 and 42) plus Barry's Cymbeline (No. 11). While the Pucks were, instead, made into smaller plates for inclusion in the Shakespeare text edition, Barry's large Cymbeline does not appear to have ever been engraved, positing what Hawkins terms "the greatest puzzle" (225).

E-visitors can again bear witness to the gallery's confrontational mixture of both aesthetics and emotion. One particularly controversial pairing, namely the Pucks by Fuseli and Reynolds, deliberately remained in the upper gallery through at least 1796, despite swaps and additions. Dias confirms that the two Pucks "entered the Gallery at the same time"—around 1790; Hawkins notes that in 1802 they still hung side-by-side, although by then demoted to the "Small Pictures" in the lower rooms (Dias, 148; Hawkins, 213). In our e-gallery reconstruction for 1796, it is easy to see how Boydell, six seasons in, still plays up the professional competition between Fuseli, rising master of the Gothic, and the late Sir Joshua Reynolds, former President of the Royal Academy and top contender for Father of the English school. It is the only example in the gallery in 1796 of different artists interpreting precisely the same subject, something Boydell took pains to avoid. For any gallery visitor, no matter how innocent of the professional tension between these two artists or how bereft of critical vocabulary, the contrast between Reynold's chubby cherub and Fuseli's muscular demon must have been electrifying. In fact, it still is.

Augmenting a visitor's knowledge of Shakespeare's plays with copies of the relevant scenes, The Shakespeare Gallery offered a uniquely impassioned experience—a visual bathos from laughter to horror and back again in the context of what historians now cite as the emergence of new public emotive displays. Boydell's paintings solicit the whole gamut of emotions across tragedy and comedy from a gallery visitor, forced to transition with a mere glance from one to the other. A 1791 review complained that "In the choice of their subjects the painters of the Gallery have been naturally led to adopt the excesses of horror, extravagance, vulgarity, and absurdity" that the reviewer goes on to attribute to Shakespeare himself (Vickers, 509). But these excesses were surely a great part of the gallery's attraction—the binge-watching equivalent of consuming all of Shakespeare in one powerful go.

Recent studies in both theatre and art history testify to the rise of public displays of unrestrained emotion during precisely the years that Boydell operated The Shakespeare Gallery. The following Thomas Rowlandson's print, for example, is dated the year the gallery opened. Rowlandson records, just as he mocks, broader transformations with regard to how people publically expressed their feelings:

Thomas Rowlandson. "Comedy Spectators. Tragedy Spectators." London, 1789. British Museum.

Click to enlarge

Suddenly it became a frequent occurrence in the theatre to see both men and women openly weeping, or even fainting, in response to a tragedy (Nussbaum). At this same time, portraitists also begin painting their sitters with broad, toothy smiles (Jones). Within the context of these larger shifts in public emotive display during the so-called Age of Sentiment, Boydell's gallery may have offered an emotionally saturated experience that stimulated a new type of public affect. No wonder Austen admits to people watching if the reactions of the crowd were becoming part of the public-art experience. With so much pathos on its walls and visitors leafing actively through catalogs to read the dramatic scenes portrayed in the paintings, the busy Shakespeare gallery surely did not solicit the hushed and po-faced reverence expected of today's museum goer.

Novelist Frances Burney, for her part, describes her first visit to Boydell's gallery in 1792 as an "adventure" centered upon the ruckus of "a mad woman" soon identified as "Mrs. Wells, the actress," who "was certainly only performing vagaries to try effect, which she was quite famous for doing" (2:275, 276). Burney's account comments on her companions rather than the artworks, remarking that their reactions to the effrontery and "burlesque humor of a bold player" (the looks of "terror...indignation") "would have been food for a painter" (2.276). In Burney's story, Mrs. Wells outrageously follows visitors and stares them down, theatrically smelling a fake nosegay of silk flowers and mumbling things that make members of Burney's party uncomfortable. Boydell's art gallery is, in Burney's account, chiefly a site of emotional provocation. Mary Wells (1762-1829) was known for cultivating a public identity whose "excessive theatricality" teetered, rumor had it, on the edge of madness (Engel, 5). Although the gallery exuded such an aura of demonstrative emotion that it might have drawn an actress like Wells to test her craft on unsuspecting visitors, Boydell's reputation for flashy controversy and gendered display makes it equally likely that Mary Wells was on his payroll (Barchas).

Back to TopVIII. Did Austen admire Shakespeare?

Yes. Jane Austen (born in 1775, coming of age in the 1790s, and publishing in the 1810s) experienced Shakespeare's rise to literary mega-stardom firsthand. She read and admired his work, referenced him in her own fictions, and saw his plays performed. As a child, Jane Austen participated in family theatricals at Steventon. A "set of theatrical scenes" was listed in the 1801 auction of family goods when the Austens moved to Bath, testifying to the ambition of their amateur productions. Perhaps as a result of this early exposure to the stage, Jane was not indiscriminate in her admiration of Shakespeare. On the 20th of April 1811, she laments a theater's last-minute change from the advertised King John to Hamlet. A few days later her brother Henry gets tickets for Macbeth so that Jane can finally see the doyenne of Shakespearian tragedy, Sarah Siddons, perform. But when he is "told by the Boxkeeper that he did not think she would," the seats are "given up" and they miss Siddons, who did perform after all (Letters, 184, and Chronology, 400). On 5 March 1814, Jane Austen sees Edmund Kean in the role of Shylock in Merchant of Venice at Drury Lane. She writes to her sister admiringly of Kean's performance but criticizes that "the parts were ill filled & the Play heavy" (Letters, 257).

Austen's own fictional people "all talk Shakespeare" in the world of Mansfield Park (published in 1814), where they rehearse amateur theatricals of their own. As Paula Byrne has pointed out, two characters in that novel, Yates and Crawford, may intentionally share names with contemporary Shakespearean actors (Byrne, 204). Moreover, scholars such as Jocelyn Harris have sounded out the strong echoes of Midsummer Night's Dream in the matchmaking follies of Emma, and pointed to parallels between Much Ado and Pride and Prejudice, especially as the Beatrice-Benedict dynamics mimic the banter between Elizabeth and Darcy.

In sum, Austen's manifold borrowings from Shakespeare, while too numerous to inventory here, are part and parcel of the scholarly understanding of her novels as extensively allusive and profoundly literary. Austen scholars agree that she was a fan of The Bard. A visit to Boydell's gallery would have influenced her perception of Shakespeare as an icon of literary nationalism in the same way that it did the rest of the nation.

Back to TopIX. How historically accurate is this digital reconstruction?

A comprehensive scholarly inventory, or catalogue raisonné, for The Shakespeare Gallery does not exist. In addition, the majority of Boydell's inventory has disappeared, with scholars agreeing that only about 40 paintings remain extant. Even so, snapshots of Boydell's gallery do survive in the form of his own catalogs. By matching up the descriptions of the large paintings in Boydell's 1796 Catalogue (where they are listed by artist and subject, including a play's act and scene number) to the few survivors and his folio prints, we were able to straightforwardly identify the images that hung in the upper gallery in 1796.

Of the 84 large pictures, thirty-one corresponding oil paintings looked at first to have survived in museums and collections around the globe (in the end, we accepted twenty-nine as originals). We started our digital modeling with the surviving oil paintings, remaining true to their recorded sizes until, after all the art was hung, we began to suspect two of them as diminutive copies of much larger originals. After further research into Boydell's payments confirmed our suspicions (the evidence is recounted below), we adjusted their sizes in the model.

The relative sizing for the missing paintings (55 out of our 84 are untraced or deemed "lost") began with educated guessing since neither the Boydell catalogs nor the Christie's 1805 sale record canvas dimensions. While the variety of dimensions among the survivors confirm that Boydell did not dictate a set size, survivors do fall into patterns or groups. We constructed a preliminary model by averaging known factors to generate templates for images with a landscape orientation and another for those with a portrait orientation. Because eighteenth-century canvasses were hand-made and dimensions of even similar works within one artist's studio varied, we "uniqued" each digital picture in the same category by a few inches to avoid a false uniformity. Giant canvases (it seems logical that these are strongly represented among the survivors, since Boydell commissioned the largest pictures from painters with the greatest reputations) were treated as outliers and not included in our averaging of typical dimension. Once we began the hanging process, proximity and wall limitations provided further clues to relative size.

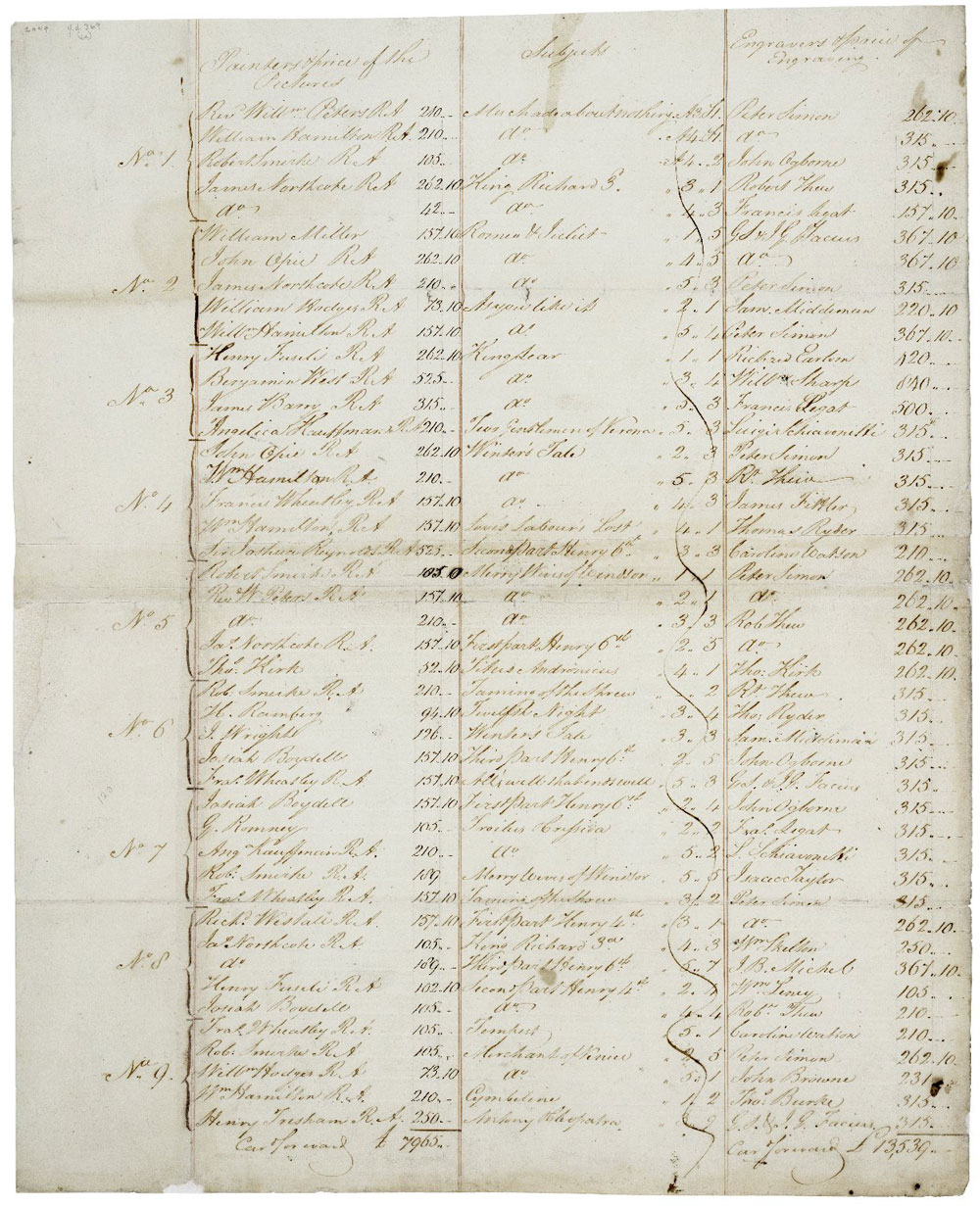

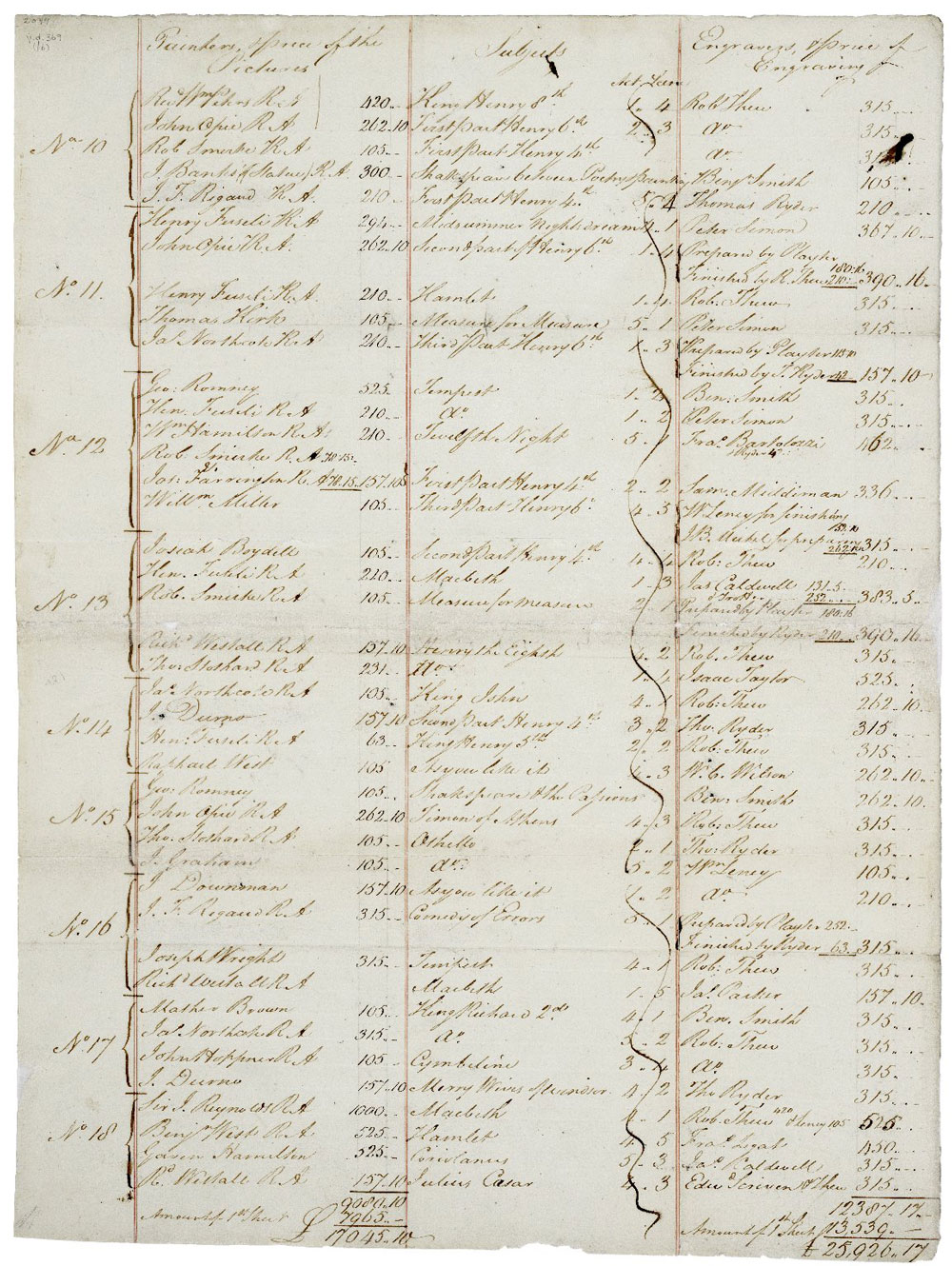

A windfall of additional historical data appeared in the form of a two-page, handwritten "List of Paintings Commissioned for the Shakespeare Gallery" that survives in the Folger Shakespeare Library, bearing an 1807 watermark.

Josiah Boydell. "List of paintings commissioned for the Shakespeare Gallery," 1808. Folger Shakespeare Library.

Click to enlarge

This compact ledger is presumed to have been drawn up by Josiah Boydell during accountings for court proceedings in 1808. It retrospectively records payments, grouped by installment numbers, for all but five of the paintings that hung in the gallery in 1796. Although the ledger does not record canvas dimensions, it provides Boydell's original cost as one further index of probable size. Of the five paintings on display in 1796 that are not named in the payment ledger, four survive; this reduced the paintings for which we had no hard data to just one. We remained cautious about sizing assumptions, aware that fees might have been bundled: when, in the first installment, Northcote was paid for two scenes of Richard III simultaneously, with one picture priced at £262 (No. 25) and another at £42 (No. 27), that did not indicate that the cheaper picture was one-sixth the size of the costlier one. In fact, a note in the Catalogue confirms that Northcote painted the picture prior to the start of Boydell's gallery (it was painted in 1786) and the smaller fee reflects a unique arrangement. Similarly, when Thomas Kirk is paid for painting as well as engraving the same image (No. 28), his modest payment for the painting (only £52.10) may reflect his commission for the picture's engraving, for which he was paid a handsome £262.10. Incidentally, Kirk is the only instance on the price list of such double dipping as both painter and engraver.

Prices for survivors did appear to reflect a mixture of reputation and format. For example, the famous Sir Joshua Reynolds demanded by far the highest fee per square inch, charging a whopping £1000 for a huge picture (No. 79) that was the same size as a painting that earned Benjamin West (No. 82)—no lightweight he—only £525. Both paintings survive to provide measurements. William Hodges, whose shipboard travels with Captain Cook honed his small-format skills, painted the smallest compositions in the upper picture gallery and was paid accordingly—£73.10 each for Nos. 13 and 43. Only one of the two 1796 pictures by Hodges survives, but after learning that their fees were identical we felt free to assume their sizes were too. Membership in the Royal Academy guaranteed an artist higher pay and Boydell dutifully records "R.A." behind the names of artists who are members. Keeping in mind format, reputation, and academy membership, the algorithms for payment became more transparent and our guesses at unknown sizes more secure.

Final confirmation of our estimates came in the form of seven surviving fragments of four paintings that were cut up: No. 35 by Romney; No. 36 by Fuseli; No. 39 by Smirke; and No. 75 by Romney. The scale of many Boydell paintings, combined with their bargain basement prices at auction in 1805, appear to have been detrimental to their survival. Too large for most living spaces, some were cut down—or even cut into multiple smaller pieces to isolate individual figures. By mapping surviving fragments onto the full composition to which they belong, one can calculate the true dimensions of a lost painting.

After a stint in an iron foundry, George Romney's "The Tempest" survives as four substantial fragments in the Bolton Museum and Art Galleries in Lancashire: "Ferdinand Leaping from the Ship" (122.4 x 88 cm), "Alonso King of Naples and Another Figure" (75.5 x 100 cm), "A Courtier" (56 x 64.5 cm), and "Prospero and Miranda" (116.7 x 128 cm). Bad reviews may have contributed to this picture's dissection. After matching the fragments to the full composition shown in the print (which provides aspect ratio), the task of estimating the original size from these fragments becomes simple mathematics:

Similarly, we used a colored Boydell print to simulate the lost picture by Henry Fuseli at No. 36 in our e-gallery, but a fragment entitled "Prospero" survives in the York Museums (63.7 x 50.2 cm). This is how small a portion that sizeable fragment takes up in the composition:

For our image of the lost picture by Roberth Smirke at No. 39 in the e-gallery, we used a small nineteenth-century copy at the Folger Shakespeare Library. But a fragment of the much larger original, showing only the figure of Anne Page, survives in the Royal Shakespeare Company's collection (106.6 x 63.5 cm). This is how the fragment measures against that larger composition:

A large portion of George Romney's Troilus and Cressida 2.2 (No. 75), which enjoyed such pride of place in 1796 at the far end of the gallery so as to make it a focal point through the arches, survives in private hands as "Lady Hamilton as Cassandra." A Christie's sale in 1929 records this fragment's dimensions as 129.54 x 93.98 cm. Here it is superimposed on the colored print in the gallery:

We discovered this fragment only after estimating the size of the Romney. Not only did the size of the generous Romney remnant tantalizingly match our estimates of the life-sized figure in the original, but Emma Hart's subsequent celebrity as Lady Hamilton (her high-profile affair with Nelson began in 1798) explains why someone after the 1805 sale would take a knife to a Boydell-by-Romney because they valued the likeness of the model more than the historical context of Shakespeare's scene. Or, putting it more generously, because someone recognized Emma, a substantial portion of this picture was saved.

In addition to providing welcome data for our sizing estimates, all of the surviving fragments make it easier to imagine the style and glory of the larger lost pictures, demonstrating that colored prints and copies remain unsatisfying substitutes. Sadly, the existence of each fragment also confirms that the original from which it was cut remains permanently "lost"—ending all hope that it has been merely lying neglected in some attic corner.

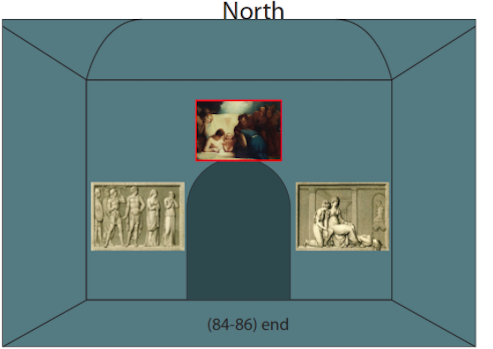

A few explanatory words about our layout rationale. In Boydell's catalogs, the paintings are not listed according to room and wall location—as was the case in the shorter 1813 pamphlet of the Reynolds exhibition. To help visitors identify the many groupings of small pictures in the lower rooms, Boydell's later catalogs do mention orientation towards the street, the nearest window, or proximity to the central chimney. Not so for the large pictures in the upper gallery, where catalog chronology is all that Boydell provides by way of guidance through the pictures.

With far less information about layout in the 1796 catalog than the slimmer one from 1813, we realized why no one had previously undertaken a visualization of The Shakespeare Gallery. Only by borrowing from our 1813 project to fill in the unknowns for 1796 were we able to generate a viable hang and a historically responsible reconstruction. For example, we knew from the 1813 show that the building's architecture dictated the starting wall for all exhibitions. [For Thomas Smith's precise architectural measurements of the building and his 1860 description of visitors' universal experience, see the "About" page for WJS 1813.] Already in 1796, when visitors reached the top of the central staircase they faced what in 1813 would be called the "North End" of the "North Room." Logic dictated that we begin the chronological hang of the 1796 show with picture "No. I" on that same starting wall. Visitor flow was thus a presumed historical constant, with the clockwise rotation from wall to wall within each of the three rooms an exact copy of the recorded movement through the identical space in 1813.

We reused our architectural blueprint of 52 Pall Mall, built in Google's SketchUp, to hang the individual walls of our e-gallery. That blueprint was already based upon precise architectural dimensions in the historical record—taken before the building's demolition in 1870.

SketchUp Video Animation

Frozen for individual wall views, cold SketchUp templates served as the basis for warmer hand-drawn tracings into which images of the paintings were digitally reinserted—as per the recipe for our 1813 reconstruction. Although the SketchUp model is accurate and even allows for a sense of movement through the space, its aesthetics do not match the eighteenth-century atmosphere we are trying to conjure.

By taking down one exhibition to hang another, we treated our virtual space as any set of curators would a brick and mortar gallery, albeit backwards in time. During the hanging process, it did not take long to discover that the Boydell canvases needed to be squeezed together much more tightly than the pictures in the Reynolds retrospective. Going back in time meant embracing a far less elegant style of hang. The contrast between the restrained Reynolds show and the crowded, brassy Boydell gallery took us by surprise: here was so much more canvas! To confirm that our tight squeeze of the 1796 pictures was historically sensible, we consulted visual records of contemporary shows at other venues, such as the Royal Academy of Arts.

Happily, one contemporary image of the interior of the Boydell gallery survives in the form of a small watercolor by Francis Wheatley of guests, including royals, attending the re-opening in 1790.

Francis Wheatley. "View of the Interior of the Shakespeare Gallery," 1790. Watercolor. Victoria & Albert Museum.

Click to enlarge

Wheatley neatly confirms the tight hang (even with only 55 large pictures during the gallery's second season, the walls already look crowded) and showed the original wall color as blue.

A note about our rendering of picture frames. The 1813 exhibition of Reynolds' work consisted of 141 pictures that the British Institution borrowed back from far-flung wealthy owners across Britain, twenty-two years after the artist's death. The wide range of loosely depicted framing styles in our 1813 reconstruction were intended to reflect how multiple owners over many decades might have chosen to frame their pictures by Reynolds in a myriad of ways. Boydell, however, remained the first and only owner of all the pictures shown in the gallery in 1796. While this did not mean every painting would have been identically framed, the Wheatley watercolor suggested that Boydell's choice of framing styles was simpler and more uniform. At the end of the 1796 Catalogue, visitors found a convenient one-page "Index To the Pictures, as numbered on the Frames." We wanted to take this rare descriptive detail to heart and place numbers on the frames of our e-gallery, but these would have been too small to decipher in the wall views. If, however, a computer user lingers their cursor on an individual painting, a number will emerge to confirm its sequential place in the Catalogue. The central text of Boydell's Catalogue used Roman numerals, while his simplified index supplied Arabic numbers, assuming the visitor's easy facility with both styles. We have done the same.

We have created a split-screen feature that allows users of our 1796 gallery to compare the curatorial hang of one specific wall to the "look" of that same wall in the 1813 Reynolds retrospective. We hope that this new navigational feature (users will find the option at the foot of each 1796 wall view) will facilitate the historical study of changing museum practices and aesthetics.

Back to TopX. Some findings, curatorial rationale, and caveats

It is with regret that our reconstruction challenges the authenticity of two pictures that looked, at first, to have survived: Francis Wheatley's Winter's Tale 4.3 (No. 18) and William Hamilton's Twelfth Night 5.1 (No. 46). Since both images have only one surviving oil painting each to match their corresponding Boydell plates, we began our hanging process with the measurements provided by the owners of these paintings, the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Theatre Royal in Bath, respectively. After several passes through the hang, however, these pictures stood out among their companions as too diminutive (47.5 x 62 cm and 68 x 86 cm, respectively).

Take the Wheatley. In our penultimate iteration of the reconstruction in SketchUp, we named this "The Problem of No. 18":

Wheatley No. 18 was the right image, because the painting matched the corresponding folio plate, but looked to be the wrong size—more like a diminutive copy, or preliminary study, than a fully-fledged gallery picture. We knew of many acknowledged copies of other large pictures, which we used in the e-gallery where originals were known to be lost. In order to hang the small Wheatley sensibly near eye level, we'd already fudged its chronological order (by placing it next to the Hodges we'd hoped to minimize its oddness). Because we did not want our subjective judgment about the aesthetics of the resulting wall to deprive the world of one more rare Boydell, we looked for better proof, which came in the form of the Boydell price list.

For all but one of the pictures on this wall, the list records original payments. The only missing payment on this wall was for the huge surviving showstopper by James Barry, the size of which is known. Putting the Barry aside, these are the recorded costs for the remainder of this wall: William Hamilton received £210.- (No. 7); Robert Smirke £105.- (No. 8); William Hamilton £157.10 (No. 9); Henry Fuseli £294.- (No. 10); Thomas Stothard £105.- (No. 12); William Hodges £73.10 (No. 13); William Hamilton £157.10 (No 14); Francis Wheatley £157.10 (No. 15); John Opie £262.10 (No. 16); Joseph Wright £126.- (No. 17); and Francis Wheatley £157.10 (No. 18). Of these men, only Wright was not a member of the Academy. Fuseli's payment is the largest and so is his painting, which survives; conversely, Hodges's payment is by far the smallest and his picture, which also survives, correspondingly diminutive. Only the Wheatley at No. 18 did not make sense. How could this Wheatley be half the size of the Hodges, if Boydell paid twice as much for it?

We therefore expanded the size of No. 18 in the gallery, and rehung the wall in accordance with these findings—digitally stretching the Wheatley copy to a suitable size justified by these facts as well as returning it to its chronological place at the end of the wall. Similar calculations and adjustments were made for the Hamilton copy at No. 46. Both pictures remain a valuable visual record of larger lost originals. The RSC's Wheatley was gifted to the Company circa 1900, while the Theatre Royal's small Hamilton was originally a gift from W. Somerset Maugham to the National Theatre. Perhaps further research will confirm whether these two oil paintings are miniature copies or preliminary studies by the artists.

We took the greatest curatorial liberties with our e-exhibition's final wall in the South Room. The division in the Catalogue between "Pictures" and "Small Pictures" suggested the separation of upstairs and down. This left three important works (listed in the Catalogue between these divisions) without a clear home: the painting by George Romney of "The Infant Shakspeare, Attended by Nature and the Passions"—the only picture that does not offer a scene from a play and gets special, numberless treatment in the 1796 Catalogue—and the "basso relievos" by sculptor Anne Seymour Damer—stone reliefs carved with scenes from Coriolanus and Anthony and Cleopatra. Were these three idiosyncratic works placed upstairs or down in 1796? Winifred Friedman points to a newspapers report that describes Damer's Coriolanus relief "exhibited over the chimney piece of the center room" at one point after its arrival in 1790 (197). In our hang, we awarded both pieces pride of place on the final wall in the main gallery. We interpreted this trio as a transitional grouping that signaled an end to the upstairs experience and sent visitors back downstairs for viewing of the remaining 55 "Small Pictures" on the ground floor.

One problem was sizing and positioning two stone pieces for which there are no other precedents in the gallery or, indeed, anywhere but in the Acropolis—Damer's apparent inspiration. With no comparables among Damer's surviving sculptures, we were forced into another educated guess. The only remaining record of these two pieces proved Boydell's own engravings, which he used as vignettes on the title pages to his folios (another clue to his view of them as prominent showpieces). Boydell's detailed prints proved as effective as photographs and, calibrating our sense of size against the scale of other Damer works and the classical reliefs she might have known from her travels, we decided to make them as wide as the space on either side of the archway allowed. Above the arch we hung George Romney's "The Infant Shakspeare," currently in the Folger Shakespeare Library. Romney's portrait of the poet as a naked infant, surrounded by attendants in the manner of Christ's nativity, seemed a fitting and playful end to the gallery's operative Bardolatry.

After our first pass at the hang of this wall's layout, however, it looked bare compared to the others: the Romney was just a tad too small to fit proudly over the archway and the Damer pieces, even at their maximum width allowed by the space, too diminutive to take command of the space. Elsewhere in the gallery the archways were flanked by taller paintings, or more works. Facing us was an unsettling amount of bare wall. We started to wonder if some "Small Pictures" had hung upstairs after all.

A little more digging exposed two pieces of data we'd missed in the enthusiasm of our initial pass. First, a conservator's report at the Folger revealed that the surviving Romney canvas had been significantly trimmed at some point in its history. By comparing the corresponding Boydell engraving, we could speculate about how much bigger the original composition might have made the untrimmed painting. Accordingly, we digitally stretched, as it were, our Romney canvas (we did not want to trade the splendid color image for a b&w print). Second, it is a truth universally acknowledged that heavy sculptures made of stone cannot be hung on a gallery wall by a mere nail or piano wire but must be supported by a base. In manipulating our digital model we'd momentarily neglected gravity. To correct this, we fussed over how these heavy stone reliefs might have been displayed (surely they'd have looked silly just sitting on the gallery floor?) and settled on digitally manufacturing a suitable base—something non-permanent that Boydell might have had constructed. Here are some options we pondered, along with wall color tests.

The resulting layout, with the plumper Romney over the archway and traditional marble supports for the Damer reliefs, proved more balanced—ending the experience of the upper gallery with just a hint of drama.

Two closing curatorial caveats about the images of the paintings used in our e-gallery. First, size. While we have meticulously retained historical accuracy (wherever known) with respect to relative sizes and original architectural features, our wall views fail to adequately convey the Brobdingnagian nature of the canvases. A modern photo of a tall Boydell expert in the Pittsburgh museum illustrates this point better than any narrative:

Finally, it is a sad fact that a mere 29 of the 84 paintings that hung in Boydell's upper gallery during the 1796 season could be tracked to museums or private collections. Fifty-five of the paintings you "see" here are considered lost, although fragments of four of these do survive. For the bulk of the missing paintings, we turned to Boydell's own folio engravings as the most authoritative surviving record of their visual content (for only a few we found copies in oil). Had we stopped there, however, the resulting e-gallery would have been dominantly monochromatic. Desirous to approximate the vibrant colors so often mentioned in contemporary reviews, we resorted to nineteenth-century colored reprints of Boydell's engravings as stand-ins for the lost original paintings. Even if some early reprints may have been hand-colored by Josiah Boydell's own colorists, viewers should be aware that copies of these prints can vary greatly in their pigmentation:

Admittedly, these reprints and later colorings move us increasingly farther from the specific 1796 gallery objects, even as we fussed about the hang, the gallery's blue wall color, and contemporary framing styles.

The result, for all of its leaps of faith, may be as good a view of The Shakespeare Gallery as our digital TARDIS will allow. We hope you enjoy your time travel to 1796!

Back to TopXI. Works Cited

Austen, Jane. Jane Austen's Letters. Ed. by Deirdre La Faye. 3rd edition. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Barchas, Janine. "Reporting on What Jane Saw 2.0: Female Celebrity and Sensationalism in Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery" in ABO: Interactive Journal for Women in the Arts 5.1 (March 2015). URL:http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/abo/vol5/iss1/1/

Boydell, John. A Catalogue of the Pictures in the Shakspeare Gallery, Pall-Mall. London, 1789.

-----. A Catalogue of the Pictures, &c. in the Shakspeare Gallery, Pall-Mall. London, 1790.

-----. A Catalogue of the Pictures, &c. in the Shakspeare Gallery, Pall-Mall. London, 1796.

Boydell, John and Josiah. An Alphabetical Catalogue of Plates… which compose the stock of John and Josiah Boydell, Engravers and Printsellers. London: Printed by W. Bulmer and Co., 1803. Google Books.

Burney, Frances. Diary and Letters of Frances Burney, Madame D'Arblay, revised and edited by Sarah Chauncey Woolsey, 2 vols. Boston: Roberth Brothers, 1880.

Byrne, Paula. Jane Austen and the Theatre. London and New York: Hambledon and London, 2002.

Dias, Rosie. Exhibiting Englishness: John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery and the Formation of a National Aesthetic. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013.

Engel, Laura. Fashioning Celebrity: Eighteenth-Century Actresses and Strategies for Image Making. Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University Press, 2011.

Friedman, Winifred H. Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery. New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1976 (facsimile reprint of her Harvard dissertation, 1974).

Harris, Jocelyn. "Jane Austen and Celebrity Culture: Shakespeare, Dorothy Jordan, and Elizabeth Bennet." Shakespeare 6.4 (Dec. 2010). Pp. 410-430.

------. Jane Austen's Art of Memory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Hawkins, Ann R. "Reconstructing the Boydell Shakspeare Gallery," in Joseph M. Ortiz, ed., Shakespeare and the Culture of Romanticism. Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate, 2013. Pp. 207-229.

Jones, Colin. The Smile Revolution In Eighteenth-Century Paris. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Le Faye, Deirdre. A Chronology of Jane Austen and Her Family. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Mannings, David. Sir Joshua Reynolds: A Complete Catalogue of his Paintings. 2 vols. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000. Print.

Nussbaum, Felicity. "The Unaccountable Pleasure of Eighteenth-Century Tragedy," in PMLA 129.4 (Oct 2014), 688-707.

Pye, John. "Sale Catalogue of the Shakespeare Gallery," in Patronage of British Art: An Historical Sketch. London, 1845. Pp. 279-85.

The Public Advertiser, Wednesday, 6 May 1789. Gale Burney Newspaper database; 10 Nov 2014.

Richie, Fiona, and Peter Sabor, eds. Shakespeare in the Eighteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

St. James's Chronicle or British Evening Post. 18-10 March 1791. Gale Burney Newspaper database; 10 Nov 2014.

Times (London), Thursday, 7 May 1789. Gale Burney Newspaper database; 10 Nov 2014.

Whitehall Evening Post, 13 March 1790. Gale Burney Newspaper database; 22 Nov 2014.

Vickers, Brian, ed. William Shakespeare Volume 6: 1774-1801. Part of The Critical Heritage series. General editor B. C. Southam. London and New York: Routledge, 2003.

Site Credits

This project is generously supported by Liberal Arts Instructional Technology Services (LAITS) at the University of Texas at Austin. We gratefull acknowledge the help and advice of Thora Brylowe, Jonathan Gross, and Ann Hawkins, who were consulted on the historical details of the gallery's workings and artists. Remaining errors are our own.

Content:

- Janine Barchas, Principal Investigator and Author

Web Design:

- LAITS Student Technology Assistants

- Alexandra Garcia, SketchUp Model Designer

- Stephanie Lawrence, Lead Illustrator

- Sarah Wang, Lead Coder

- Audric Ganser, Coder

LAITS Staff:

- Suloni Robertson, Project Manager, Art Director

- Ryan Miller, Web Developer

- Lauren Moore, Web Developer

Special thanks to:

- Joseph C. TenBarge Jr., Director, LAITS

- James Henson, Associate Director, LAITS

- Tim Fackler, Senior IT Manager, LAITS

- Randy Diehl, Dean of Liberal Arts